The telephone

rang. It was a Sunday evening and it had just turned 10pm. The

Jones family were watching the television in their stone cottage situated in a

quiet Cotswold village. Just over an hour later Jones was still watching

the television. This time it was as he was accelerating through 200mph

and heading North in a VC10 tanker. The television screen was that of the

aircraft CCTV which allowed him to monitor the undercarriage as it

retracted. It also enabled him to monitor the receivers as the tanker

refuelled them. Jones, an air engineer on 101 Sqn, based at RAF Brize

Norton, was on ‘standby’. Everyday throughout the year two tanker

aircraft complete with two crews were on standby and could be called at a

moments notice to give air-to-air refuelling support to air defence

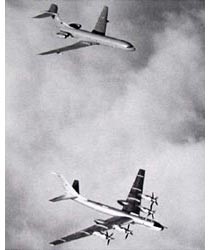

fighters. On this occasion it was to intercept two Russian Bears, the

NATO name for an ageing yet very versatile four-engine bomber. At that

very moment two of them were being tracked on radar as they headed south-west

from the northern coast of Norway.

The crew of the VC10 tanker, two pilots, a navigator and an air engineer,

worked quietly in the semi-darkness of the cockpit. Firstly they

concentrated on the take-off and climb checks, then on completing calculations

such as the length of time it would take to rendezvous with the air defence

phantom, and how long they would be able to remain on task. Jones also scanned

a bewildering array of instruments methodically checking them to ensure that all

the aircraft systems were serviceable; Checks that he would repeat many times

during the flight.

First the fuel system, which contained over 20,000 gallons of fuel.

Already he was transferring it in preparation for air-to-air refueling.

Next, the engine instruments of the four Rolls Royce Conway engines that could

produce 100,000lbs of thrust and which had accelerated the tanker to a speed of

nearly 500mph at a height of 31,000 ft. Then followed the powered flying

controls and electrical and anti-icing systems. They were operating

normally except for a slight load imbalance on one of the generators.

Jones stopped his checks and checked the aircraft speed; it was a shade too high, so he inched back the engine throttles to reduce it. Then he continued his checks of the remaining systems. The air-conditioning, pressurisation, hydraulic and oxygen systems, they too were operating normally. He glanced across to the navigator’s panel to check their position; they had just left the Isle of Man. On the starboard side, Jones could make out the lights of Liverpool and yet still further north, Preston. The air was so clear and the lights were so bright, weaving intricate patterns on the ground below, that he thought it was worth getting airborne for the view alone.

His thoughts were interrupted by the voice on the radio giving a situation report. The Bears were still heading south-west in the direction of the Faroes, 250 miles north of Scotland. What their plan was, was anyone’s guess. They could be on a transit flight to Cuba, for they had phenomenal range. Alternatively, they could simply be testing the reaction of the UK air defence system. It wouldn’t be the first time that he had accompanied a pair of Bears as they flew low over the North Sea and then simply turned around and headed home.

Well over an hour had elapsed since they had taken off from Brize Norton and soon they were to to be joined by a 43 Sqn Phantom from RAF Leuchars. The captain called for the tanking checks and shortly afterwards Jones trailed the 80ft long fuselage mounted hose, monitoring as it slowly trailed into the airflow. They could have used either of the 50ft wing hoses, but Phantom pilots preferred the centre hose as it was capable of transferring 450 gallons of fuel per minute.

The Phantom pilot called when his radar had locked onto the tanker. Ten minutes later Jones could see its navigation lights on the CCTV screen and two minutes later it was formating on the tankers’ port wing. The captain cleared the Phantom to go behind the centre refuelling hose. Jones checked again that the lower rotating beacon was switched off as it would otherwise distract the pilot of the Phantom.

‘Steady astern’, Jones informed the captain when the Phantom was positioned some 20ft behind the centre hose. ‘Continue on the lights. Red out’ ordered the tanker captain. Jones switched out the red light which, like a traffic light, informed the receiver aircraft whether they could make contact or not. Jones gave the crew a commentary as the Phantom pilot slowly gained on the tanker. ‘Closing, steady approach, close on the hose, contact, green on, fuel flows’. The Phantom pilot had made contact on his first approach and now they were linked together by an 80ft long hose. Just like a baby attached to its mother by the umbilical cord. ‘Some mother’ thought Jones, ‘weighing in at just over 333,000lb. Some baby too, guzzling fuel at 450 gallons a minute at over 400mph!

The Phantom took 5 mins to refuel, and as the flow meter dropped to zero, Jones indicated to the Phantom pilot that they were full, and the Phantom dropped back. When the hose was fully trailed, the Phantom probe disconnected from the tanker’s hose and the Phantom moved to the tanker’s starboard side. They were to repeat this process two more times during the course of the night and on each occasion nearly 2,000 gallons of fuel would be transferred. Jones wound in the centre hose and reset his fuel panel.

Just then, the

voice of the controller informed them that the Bears were now only 100 miles

away, still heading south-west. We will intercept them in less than 10

mins calculated Jones. The Phantom went into reheat and accelerated in

the direction of the Bears. The TACAN range, which gave distance between

the Phantom and the tanker gradually increased. It then stopped

increasing and began to reduce as the Bears and the Phantom converged on the

tanker.

’20 miles. 10 degrees port’ reported the navigator as he scanned the radar

screen. Four pairs of eyes searched the darkness ahead of them.

They were quickly rewarded. ‘Visual’! exclaimed the co-pilot as the

lights of the converging aircraft became visible. Shortly after, the

tanker joined the formation the Phantom on the lead Bear and the tanker on the

one in trail. This was in case the two Bears decided to part company as

it enabled each Bear to be shadowed independently.

So the formation continued; not a word was exchanged between them. This

was the 22nd Bear Jones had intercepted, yet they still fascinated him, not

least the tail mounted gun. It would certainly make ones eyes

water! He checked his watch; another half an hour and the Phantom would

need to be refuelled again.

Without warning the two Bears banked sharply towards their escorts, but as they

always maintained 1000yds separation, this was not an embarrassment. ‘What

now?’ thought Jones as they too changed course. The Bears stopped turning

when they were heading north-east. ‘Surely they are not going home

already?’

Jones’ thoughts were interrupted by the Phantom requesting further fuel uplift

and in less than 5 minutes it was in contact and fuel was being transferred.

At the same time as they continued formating on the Bears.

When they were some 100 miles north of Scotland the ground controller ordered

them to orbit in their present position. They would be ideally placed

should the Bears decide to return. Jones quickly calculated the

economical loiter speed and adjusted the throttles in order to maintain

it. So the tanker and the Phantom remained for nearly and hour. The

Bears continued heading north-east; they were heading home. Assured of

this the controller ordered the tanker and Phantom to return to their

respective bases. Before leaving the Phantom had a final fuel transfer.

All at once they felt tired. It had turned 2am. The elation of the

intercept gave way to quiet satisfaction. Soon each crew member was

locked into his own thoughts.

The silence was occasionally interrupted by a request

for a change of heading or an update of buffet speed.

‘Was it really 2 years since I joined 101 Sqn?’, mused Jones to himself.

So much had happened. The return of 22 Lightnings from Saudi to England,

the world record non-stop flight of a VC10 tanker from England to Australia and

the deployment of Phantoms to the Falklands. Not forgetting the flights

to Canada, USA, Cyprus and Sicily. All this in addition to North Sea

towlines and ‘standby’. As he mused he continued his methodical checks of

the many instruments.

An hour later the flight deck activity increased as they prepared to

descend. Half an hour later they had landed; it was approaching

4am. With this in mind they had not used reverse thrust as the extra

engine noise would wake up the local community. In spite of this, there

would still be complaints of the noise. Ironic, thought Jones, if only

the complainants knew why they had been airborne.

One final task before they finished, the ground crew debrief. Only one

snag so it did not take long. Dawn was breaking as he drove home; he

couldn’t help wonder what the new day would bring.

Original article written by ‘Lofty’ Taylor and published in the Air Engineer

magazine 1988