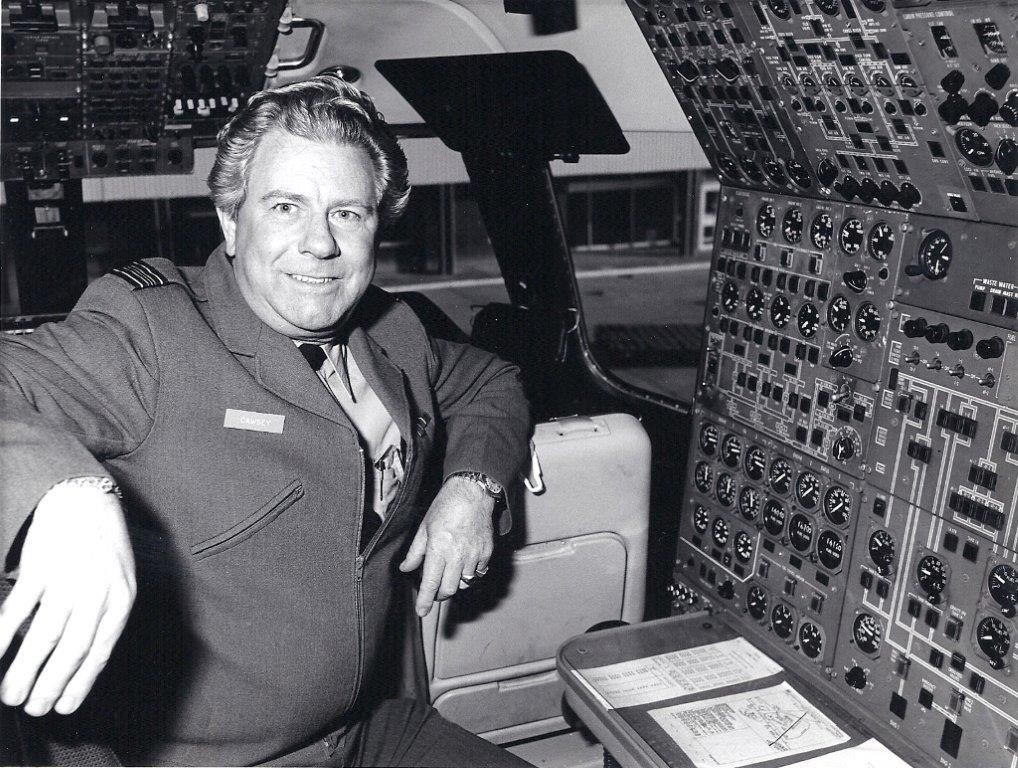

By Sqn Ldr Michael J Cawsey GD Eng RAF Rtd.

Chapter One – First Tour for a Direct Entry Flight Engineer

A strange title but nevertheless true, I served thirty seven and a half years in the Royal Air Force, flew over 12,000 hours in seven major types, but my home stations were all in England.

Let me start with enrolment at Cardington in March 1950. I had been an ATC Cadet in three different squadrons 263 at Acton Technical College, then secondly 1413 Ealing Squadron at Ealing Library and finally 342 Ealing Squadron in Hanwell. I was a cadet FS and had been to camps, experienced flying in a variety of types, and obtained a gliding certificate in Daglings and Cadets at RAF Halton. During this period I also learnt to shoot and became quite proficient at .22 rifle target shooting under the influence of an instructor from the Ealing Police Rifle Club. I purchased my own rifle, an ex-German military bolt action .22 Mauser. Not quite up to the high standards of the Martini Action target rifles generally in use, but with competition sights on it I did remarkably well, and I subsequently took this weapon into the RAF with me and used it in the Wales and Monmouthshire League competitions.

My appetite for the RAF and flying had been whetted and I made an application to join the RAF as aircrew. The letters PNSEG on the application form indicated that I wanted to fly at all costs and any trade would be acceptable. After attending the aptitude tests at RAF Hornchurch I was offered SEG, and I elected for and was accepted for training as an Air Engineer.

Back Row: James Mutsaars John Land David Johnson.

Front Row: Maurice Pavett Michael Cawsey Michael Laker

I enlisted at RAF Cardington on 27th March 1950 and met the other five who were to form the initial part of the course intake at No 4 School of Technical Training at RAF St Athan. John Land, Maurice Pavitt, David Johnston, Mike Laker and James Mutsaars. Our Course No 12 consisted of three phases each scheduled for six months, first basic where we did all of our initial service training, metal bashing and academic work. Plus, of course Aircraft Recognition, sport PE and basic aircraft systems. For phase two of the course, 12 ex-tradesmen who were all Fitter IIs, Airframe and Engines and even an Electrician, joined us. They were invariably ex-RAF Apprentices, and whilst they were clearly the senior men they were not made course leaders a job retained for the new boys, but they were placed in charge of our billets. On East Camp we lived in wooden huts heated by two Tortoise stoves, and that was another learning curve keeping them lit on the frugal fuel supplies.

On the second phase we concentrated on system components, whilst the final phase was to look at Gas Turbine Engines, and Aircraft Systems, Performance, and even Engine Running which was practised in a Miles Magister, an Avro York and a Lincoln. The flying experience consisted of four exercises in a Lincoln to handle the controls, and practise Log Keeping. This experience amounted to fifteen hours of which nine was a single night flight!

The time was early in 1951 and clearly with the changing situation in the Far East and the planned introduction of the English Electric twin-jet Canberra bomber, the demand for Flight Engineers was about to change dramatically. Our course was abridged and we passed out with a Brevet (E Badge) but still as Cadets with the large arm badge. It had previously been the practice for the cadets to be made up to E IV towards the end of the course, and move into a separate mess as a first stage in their NCO training, and then to have the Brevet presented on graduation. An E IV wore a single star within his laurel arm badge, the ex-tradesmen having a pale blue stars, and the Direct Entry Engineers had a white ones. There was also a pay differential with the ex-tradesmen being called Engineer (A) and we were, of course, (B) this anomaly was eventually removed some time in 1968 when all of the (B) engineers were allowed to sit an examination and remuster to Air Engineer (A).

On leaving St Athan, the courses were posted to a holding squadron prior to attending an Operational Conversion Unit for Type training. The Short Sunderland, Handley Page Hastings and Avro Lincoln were the main types. I was posted to RAF Hemswell where I was attached to 97 Squadron. We arrived as a total anomaly, cadets with a Brevet, we were a sort of outcast. Clearly in need of an Aircrew Mess, which only existed on one RAF station, maybe a stage above the Airmans Mess, yet not promoted to Sgt. We lived in a Drying Room, and ate behind a partition in the Airmans Mess. The Squadrons did not really want us, although we did a bit of flying as 2nd engineers, and some practical training in the hangars, even learning how to service the Tiger Moth which was present on all squadrons for pilots to keep their hands in on light aircraft. My companions at that time were Dennis Crowson and Fred Coates, and we spent many days working on the Station Farm or keeping out of sight there.

Shortly afterwards our promotion to Sgt came through backdated to when our Flying Badge was awarded, which was 8th May. Around about this time there had been a very significant increase in the pay scales and we were all highly delighted with our back pay. By the time my Type Course started at 230 OCU, RAF Scampton in September 1951, the confusing aircrew ranks introduced in 1946/7 had all but gone.

For the record I will try and clarify them, and their insignia; a cadet simply wore on the upper arm a light blue embroidered laurel wreath with an eagle facing rearwards above it, an E IV had a single star in the middle of a pair of laurel leaves surmounted by a woven eagle, an E III had two stars, an E II had three stars, and an E I had three stars and a Crown above the eagle and was equivalent to a FS. The Master Engineer had a Coat of Arms badge within the top of the laurel leaves, and the eagle was placed where the stars had been. As a Warrant Officer equivalent rank badge it was worn on the lower sleeve as it still is today. For the purists the badge for Warrant Officers remained, but was later made from a Navy Blue Cloth and the woven eagles were replaced with gilt ones.

On the first day of

the OCU all of the crewmembers gathered in a large room, a mixture of ages,

experience, ranks and trades. There were first tourists and the more

experienced youngsters and those more mature. Ranks were Sgts through to Flt

Lts and trades being Pilots, Navigators, Signallers, Engineers and Gunners.

Those who had been around and knew the score, quickly sorted themselves into a

crew, whilst the greener ones found themselves wandering around asking who

still needs a navigator or whatever. This had been a traditional method of

crewing up and had worked well as a system over the years.

During my time at Scampton on the course, I first became aware of the realities

and dangers involved in flying. An overconfident pilot shut an engine down for

a high coolant temperature on a solo flight, his landing was not that spectacular

and as a result he attempted the impossible – an overshoot from the three

engined landing. He left the runway traversed the airfield, clipped a hangar

and came to rest in the 25 Yard Range where the aircraft exploded and burnt.

Sadly all of the crew did not survive and this tragic accident brought the

reality of the saying “I learnt about flying from that” home to me. If the

Pilots Notes, as they were then, say it is not possible to go around from a

missed landing on asymmetric power then that is a fact, the word must or must

not was mandatory in the handling instructions.

Later on during the course my crew headed by Flying Officer John Shingler managed to leave the runway after four engined landing during a Saturday morning solo exercise. Out on the airfield were two teams playing football, our Lincoln trundled along parallel to the goal posts, with players scattering in all directions. The starboard outer propeller managed to turn the wooden crossbar into many fragments as the rotating blades went CHOP CHOP CHOP along it, pieces going in all directions.

My OCU was actually done with an arm in plaster, as shortly after starting it I had an accident with my newly acquired ex-WD 350 Ariel Red Hunter motor cycle. I was out at Dunholm Lodge airfield following a very experienced motorcyclist called Junior Dunstan, also a flight engineer on the course, but on a corner and travelling too fast, I ended up on the wrong side of the road and clipped a car coming in the opposite direction. From my position in the bottom of a muddy ditch I clearly remember my first thoughts were are my teeth still intact as I ran my finger along them? They must have been good teeth developed from school milk as I still have them 50 years later.

After a couple of

days with my very swollen and painful wrist strapped up, and X-rays at RAF

Nocton Hall, my arm was eventually encased in a plaster cast due to a fractured

scaphoid bone in my left wrist. The crew had to assist in getting my kit on

board, and I sat at a very strange angle in order to follow up on the throttles

for take off, but we got by. I was exceptionally allowed to continue flying, as

there had already been a loss of an engineer from another crew on the same

course.

The definition of a Flight Engineer’s duties and responsibilities was given in

an Air Ministry Order. A262/42 as amended by 681/42.

To operate certain controls at the engineer’s station and watch appropriate

gauges as indicated in the relevant Air Publication. To act as a pilot’s

assistant on certain types of aircraft, to the extent of being able to fly

straight and level and on a course. To advise the captain of the aircraft as to

the functioning of the engines and the fuel, oil and cooling systems both

before and during flight. To ensure effective liaison between the captain of

the aircraft and the maintenance staff, by communicating to the latter such

technical notes regarding the performance and maintenance of the aircraft in

flight as may be required. To carry out practicable emergency repairs during

flight. To act as a standby gunner.

In reality that definition provided a sound basis for what evolved. The flight

engineer was a pilots assistant, technical supporter, systems handler,

limitations minder in addition to being able to relate to the ground crew, and

if necessary carry out simple repairs. He was also required to be competent to

service and replenish the aircraft in the event that it landed away from

support.

Not listed in the

AMO, was a most important function which is Weight and Balance. All aircraft

were weighed periodically, and their Basic Weight and Moments listed. Once

allocated an airframe, the weight of the crew, stores of fuel, bombs, and

ammunition had to be added to the basic weight, and their moments calculated.

The moments divided by the weight would produce a figure, which was the Centre

of Gravity (C of G) for take off. This had to be within the limits published

for the aircraft type in order for the machine to fly with good control

response and handling characteristics.

Before flight an extensive external inspection was carried out, checking on the

overall condition of the machine, tyres for wear, cuts and creep, generally for

oil, fuel, hydraulic and coolant leaks, security of control surfaces, and the

function of all external lighting. Ensuring the removal and stowage of control

locks and jury struts, pitot head covers and static plugs. Once inside all

emergency and safety equipment had to be checked and stowed, Elsan secure and

closed, control runs unobstructed, emergency hatches secure and upper surfaces

and filler caps secure, hydraulic reservoir level correct and accumulator

pressure checked.

On the flight deck or cockpit as it was then, the emergency air knob had to be wire locked. The supply of spare fuses and bulbs, Very pistol and cartridges checked, then all switches and lights were checked, and system controls placed in the correct position. Fuel and oxygen contents had to be checked and recorded in the engineers log. I can remember at the Lincoln OCU each student had to sit in their flight seat and be able to touch any control or switch nominated by the instructor whilst wearing black goggles. During flight a log was maintained of all power settings, the indicated and predicted fuel consumption, and fuel remaining, calculating range and endurance information.

The engineer, in

response to pilot demands carried out Landing Gear and Flap selections, but

pilots operated their own control for the Bomb Doors. Engineers started

the engines and carried out the Run Ups and Power Checks when required. Apart

from taxiing and initial take off power application when asymmetric power was

invariably needed to control the swing, and maybe the landing, all in flight

power settings (cruise control) and propeller synchronization were carried out

by the engineer, listening to the beat or noting shadows between the props.

Coming back to real time we graduated as a crew and were posted to 12 Squadron

at RAF Binbrook. The Conversion had taken four months and we had flown 96

hours, almost half at night, which was going to be the pattern for future

flying in Bomber Command. My time on “Shiny 12” was only three months, in that

time I flew with six different skippers, learnt about “Gee” bombing systems,

did an airtest for the first time and flew a sortie out to a Weather Ship,

where we dropped a container of mail, and then ended up on three engines for 4

hours. High Level Bombing and Air to Sea firing were regular events; I

physically flew the aircraft for about 14 hours and added another 77 hours to

my Logbook.

This rapid escalation of experience was brought to a close with a couple of delivery flights to RAF Waddington, on one of these I was with a pilot called Bob Harrington and when we arrived at the aircraft I discovered one of the prop blades had been bent at the tip by a vehicle probably a tractor. We discussed the situation and I sent for a couple of large hammers and the tip end was brought back into line and as it was a very short hop over to Waddington and we were very light we agreed to take it. These deliveries were brought about by the introduction of the Canberra into RAF Service and the Binbrook squadrons were the first to be equipped. Flight Engineers, Signallers and Gunners were of course not needed on this new machine and we were all put up for disposal.

At Binbrook one of

the pilots on 12 Squadron was FS Michael John Cawsey, exactly the same name and

initials as mine, however he was married and lived in Married Quarters, and I

lived in the Sgts Mess, all mail was handled by the RAF Post Room!

Whilst at St. Athan, I had learnt to dance in the City Hall at Cardiff courtesy

of the girls from the Coal Board who were short of partners. Being near Grimsby

I started dancing at the Gaiety Ballroom and met a young lady Elizabeth Hinds,

who sent a rather personal letter to a Sgt MJ Cawsey, RAF Hemswell etc. This

letter was delivered, in error, to the other Mike Cawsey’s Married Quarter.

Needless to say it was opened by his wife, and caused a great upset when he

came home for lunch and denied all knowledge of its contents. I eventually got

a very crumpled letter later that afternoon when all had been sorted on the

domestic front. Liz was an excellent dancer and with a slim figure and great

looks was the winner of the local Beauty Queen contest. We were engaged for a

while, and even kept in touch after the engagement ended, I had the ring

returned to me and that provides another story later.

The early Canberra was Avon powered and at that time the engine inlet guide

vanes were simple two position ones. The thrust generated is controlled by the

pilot’s throttle demands, but high power is not instantly obtainable until

these vanes have changed position to allow a maximum airflow into the engine.

One of the earliest accidents to the Canberra occurred when a pilot tried to

overshoot in a snowstorm, his demand for a very rapid increase in power, caused

an uneven response from the engines, higher thrust on one side than the other,

and with the low airspeed the aircraft became uncontrollable and crashed. After

I left Binbrook my own original crew John Shingler, Jim Pemberton, and Harry

Hawkes were all killed when, after inverter failure and loss of some

instruments their aircraft flew into Sixhills at Market Rasen on 10th November

1952.

Posted back to Hemswell and 97 Squadron I was crewed up with Sgt Ken Marwood. Ken was a masterful pilot and really believed he did not need any help from me. We had a number of disagreements before settling down to work well as a team. He had a stable crew which produced exceptional bombing results and that was the yardstick of success. I remained crewed up with Ken until he went to be commissioned in early 1953. I did not believe I was being utilised to best of my abilities, and had ideas of getting a posting onto Hastings or even Washingtons, so I applied to change aircraft type.

At the time, the Squadron Commander was Sqn Ldr Terrence Helfer, sadly, I cannot remember his decorations, but he certainly had some, and always wore a black flying suit when the rest of the RAF wore grey! He called me in for an interview and really worked me over verbally. At the end he said well Cawsey the choice is yours, as a result of the Lawrence Minot Bombing Competition, your crew has been selected to fly to the United States of America to participate in a bombing competition. You can have this application back and go with us, (he was going as well) or I can process it and you may or may not get a posting but you will not have this trip. Of course I rescinded the application and went back to the crew room to spill the beans.

On the squadron we had eight airframes, and ours was RA713 “B” this aeroplane became a very personal thing and we nurtured it and always wanted the latest and best fitted to it. The Bombing Competition was the Strategic Air Command Bombing and Navigation Competition, an annual event. Two Lincolns from Hemswell and two Washingtons from RAF Marham were going, and it was being held at Davis Monthan AFB in Arizona, the hosts were the 63rd Bomb Squadron.

Preparation got underway, the engines were replaced if necessary, new wheels fitted, the aircraft serviced in anticipation of being away for a month. In addition two 400 gallon fuel tanks were fitted in the bomb bay and a pannier to carry spares and tools for the trip. The Overload Fuel tanks, which increased our capacity to 3650 gallons, were piped into the normal fuel system inboard tank. There were no tank selectors on the Lincoln, fuel feeding by gravity into a collector tank, which fed the engines, this in turn meant that transfer could not be started until the main inboard wing tank level had dropped enough to accept a transfer and the outer tanks, fed by gravity, emptied first.

On the Atlantic crossing we stopped at Keflavik, then onto Ernest Harmon AFB, our aircraft had no problems with the fuel transfer, but we did spend 6 hours out of the 10 on the flight in cloud at about 1500 feet. With no Anti Icing or De Icing fitted we had little choice but to stay low, and with our altimeter set on 1013.2 we later discovered the atmospheric pressure at the centre of the depression was 980 so for some of the time we had been flying at about 500 feet above the sea in cloud. After our arrival in Stephenville there was no sign of the other Lincoln RA677 flown by Sgt Split Waterman. Eventually it arrived but desperately short of fuel. Trouble with the fuel system transfer and the loss of nearly 400 gallons of fuel due to a leaking connection due to a misaligned olive, had caused them to reduce power and fly slowly in an effort to conserve what little fuel they had. A very primitive system, which would not meet any safety standards in this day and age, where the aircraft was committed to continue the crossing on the assumption that the transfer would take place!

Modern design

concepts would reverse the order in which fuel was taken from the wing in order

to provide a relieving load and reduce stress and upwards bending in the wing.

For the flight from Earnest Harmon we did a leg to Westover AFB Massachusetts

in just over 5 hours, then onto Davis Monthan on that final leg we flew for

almost eleven hours, at about 5000 feet and had a superb view as we crossed the

various states.

On arrival we discovered that the Lincoln did not have the range to complete

the full route set for the competition even with our overload tanks, so the

competition route was suitably shortened for us, and our results became

comparative against the B29s, B50s and B36s.

Arriving on 30th Sep, we left again for the UK on 22nd Oct. Giving us just over three weeks at Davis Monthan for the competition and recreation. Dealing with the competition, we did three practice sorties and a final airtest. A flight to Sathurita bombing range near Phoenix where we did some high level practice live bombing, releasing 2 x 200 pounders. The next one was a radar cross country to Kansas and Dallas lasting nearly 10½ hours, and our final practice was bombing at the Wilcocks Range.

After the drop, Sqn

Ldr Helfer took the controls, and treated us to a low level tour of the Grand

Canyon. Our major problem turned out to be the new VHF radio, installed

especially for the trip, it had been borrowed from an Oxford aircraft and was

in fact some old Lend-Lease equipment, as I seem to believe the Washingtons

were. After breaking a number of ATC instructions and having a violation filed

against us, the USAF decided we needed a special briefing, and flew in an Air

Traffic Control Officer to defuse the situation.

The dawn of the competition was the following Monday, dusk would be a better

description as our Take Off time was 2130 hrs, on the three nights we flew

Monday, Wednesday and Friday. (The other aircraft flew the alternate nights.)

We carried a USAF Major as Observer, and 2 x 500 pound bombs. We were the first

off each night, from a 2500 ft field elevation; we then had to orbit climbing

to clear the mountains at 15,000 ft, before setting course. Our sortie lengths

were 12.20 on the first night, 12.30 on the second and 12.55 on our final

night. That was more than a typical months flying time in the space of a working

week, and we needed some rest.

Five hours after TO we arrived at Kansas City and completed a simulated bombing

run by radar, 2½ hours later the same exercise at Dallas. Our (blind

bombing) radar was known as H2S, it had a rotating antenna in a very large

cupola under the fuselage, and the presentation was on a circular scope. The

Radar Navigator lived under a black curtain during the run ins. Our simulated

run scores were calculated by ground radar plots from the moment we called

“Bombs Gone”. Our results were consistent at 250 yards for every run in the

contest and this was a superb achievement. The next target was at Phoenix

just 3 hours away and this was a ground assessment of a visual bombing attack

on a drainpipe on the corner of a bank.

The final task 2 hours flying from Phoenix to a visual desert range at Tucson, to drop the 2 x 500 pounders before returning to Davis Monthan AFB. We had not been able to calibrate our Bomb Sight and as a result the visual bombing scores were not up to our UK achievements. That said, our crew results were the best RAF one, and on a comparative basis against all entrants we were in fifth position. The Americans had great difficulty in grasping the fact that mere NCOs captained both of the Lincolns and that the crews both contained officers.

The Merlin engines

made a noise which was a great attraction, and drew crowds whenever engine runs

took place, on one occasion an over enthusiastic member of our ground crew

operated the boost over-ride to obtain more power and noise but he forgot that

the pannier was laying below the belly. It was lifted and flew rearwards and

hit the leading edge of the tailplane causing considerable damage. Luckily this

incident happened shortly after arrival, the USAF technicians allocated to

assist us quickly cut the damaged skin and ribs away and created an immediate

repair scheme, with handmade ribs and a perfectly fitting new leading edge

section, the aircraft was quickly back to Combat Ready in plenty of time for

the competition. The Observers who flew with us were impressed with our

manoeuvrability and approach techniques, and of course the way we worked

together with little unnecessary chatter.

Whilst there, we had an great social life, being invited into many homes, and I

stayed in touch with a USAF flight engineer for many years and he even turned

up at my parents home for Sunday lunch without any pre warning. The drinking

laws in Arizona were strict, with a minimum age of 21 to buy alcohol, Ken was

OK at 22 but he didn’t look his age and I was only 20 and five months, so we

had a few problems when out for a drink. I’ve Got Sixpence became our

theme song, and we sung for our supper quite often. We were very short of

dollars, only being allowed to draw $1.50 from our pay and about $3.00 in

allowances on a daily basis.

On one of our off days, we went to the border at Nogales and crossed into Mexico, I remember stopping a few times in order to take in the scenery and take pictures. We had a good look around the border town and I believe only one guy from the RAF detachment got carried away with the offer of “You wanna buy my sister”. We discovered this after returning to the US side of the border and dashing to the toilet in the basement of a military building. There was a very large Medical Orderly there who demanded to know who had had “Connections” when this guy admitted he had, he was ordered to drop them and a very large hypodermic syringe connected with his rear end. This was normal US Military treatment for the prevention of venereal disease, and put our simple ET (early treatment) Room to shame.

Our route home was similar to the outbound one. 10 hours to Westover AFB for a night stop, then 4.20 to Goose Bay in Labrador, and finally a direct flight to Hemswell taking 11.05. My logbook tells me we flew 117.15 in 29 days, and our worst technical problem was the autopilot on the final leg. A great experience and achievement for a young crew, but thinking about it we were not really the youngest around for National Service Aircrew had been introduced and we called them our 18 week wonders, for they were flying aircraft like the Lincoln 18 weeks after joining the RAF!

A Lincoln returned from a sortie one day and landed on 3 engines, with the No 4 engine shut down and feathered to minimise the drag. When the crew were interrogated in order to establish the cause of the engine failure, they did not have any idea. “It suddenly feathered itself” so we came home was the statement. Once in the crew room it was fairly easy to find out what had happened. The engineer often eased himself out of his folding seat at the request of the navigator, and slid down into the nose compartment either to select or arm the bombs or set wind onto the bombsight computer. Invariably wearing a parachute harness loosely fitted. On this occasion he had eased down into the nose, carried out the Navigators requests, and returned to the cockpit. His harness had caught he No 4 Pitch control (RPM) lever and as he moved forward he had inadvertently moved it downwards and through the feathering gate causing the engine to stop rotating. Neither the pilot nor engineer understood what had occurred so they did the best thing and returned to base.

Another incident I shall never forget concerned a very keen 18 Week Wonder who wished to be trained on the Tiger Moth including the hand swinging of the propeller for starting. After a suitable period of training and explanation, I left this fellow with a Tiger Moth in the middle of a hangar to practice his procedures and inspections. Some time later he appeared at the crew room door ashen faced saying it’s live. Well a live prop is a liability and very dangerous, I accompanied him back to the Tiger Moth, the cowlings were open, fuel off, magnetos off, and throttle closed. I stood firmly in front of the engine, pulled the prop into position and gave it a brisk tug. To my horror and astonishment it was now live, kicking, and actually running it had burst into life despite my checks on Fuel and Magnetos.

As the crowd gathered (engine running in a hanger was not an authorised procedure) I rushed around to the left side of the cockpit and slammed the throttle fully open in an effort to stall the engine. Sadly it responded, I slammed it shut and looked up. He was standing by the right side of the engine with a cup-like object in his hand, at this moment it all became very clear. I shouted above the engine noise PUT IT ON, and as he leant forward arm outstretched behind the propeller, and did so the engine stopped much to my relief. The magneto switches route via the contact breaker cover, and if the cover is removed the magneto IS LIVE. He had been trying to observe the action of the impulse starter whilst turning the engine when it kicked him. The fuel had been on whilst he did some checks earlier and the carburettor was full of fuel. I suffered a lot of leg-pulls over that one but again I learnt about magnetos from that incident.

The Merlin whilst

generally very robust and reliable had to have its lubrication system carefully

primed after it was newly installed, and it may be that this next incident

could be attributed to that procedure. Ken and I were tasked with doing an

airtest after a No 2 Engine had been changed, it was late afternoon on 3rd Feb

1953, these flights invariably were carried out at max power for Take Off. We

had three options 3000 RPM +12 lbs Boost at the gate was our normal setting.

That is a manifold pressure of 12 psi above standard atmospheric or 54 inches

of Hg (Mercury). If the throttles were pushed through the gate about +18 lbs

(66.5 Ins Hg.) depending on field height would be supplied, but if the Tit or

Override was operated, the boost went to +21 lbs (72.68 Ins Hg.) It was

used when the aircraft was fully loaded, or other conditions were not

favourable. Or of course, to make an impression on a display flight with a very

lightly loaded aircraft when it positively leapt into the air.

On this take off we were well down the runway when a loud bang and power loss

occurred. No 2 engine had seized and later we discovered that it had thrown a

connecting rod through the crankcase. Ken brought the aircraft to rest, and the

man from Rolls Royce was not in the least concerned, saying it was a known

problem.

On another occasion on Take Off the main wheel flange, which forms a removable rim decided to fracture. The tyre simply changed position, and was like a hoop around the oleo leg. The aircraft sank onto the hub, which dragged along the runway, and caught fire as it was being worn away by the runway surface. With the noise and vibration, the lowered wing and reduced acceleration, the TO was abandoned and the aircraft stayed on the runway due to the skill of Ken in keeping it straight. The fire was extinguished and the long-term damage was limited to the brake hoses, wheel and tyre.

Late in February 1953 Sgt Graham Smith arrived on 97 Squadron, posted in from Waddington to replace Ken. He was a superb pilot as well and we became great friends. I see from my logbook that we often flew in the Tiger Moth together, as well as in the Lincoln, which now seems to have assumed the role of Gee-H Bombing.

Bomber Command was a regular spoiler of weekends with exercises on Saturday nights. They came under the code names such as Bulls-eye, Backchat, and so on. All of these exercises were started with a large preflight meal, and finished with the great British fry up. The Exercise Briefing followed the preflight meal; many of these exercises were flown with a maximum command effort, all aircraft on the same route in darkness and without Navigation or Resin lights [Editor’s note, coloured lens lights similar to Formation lights]. When the exercise was complete each aircraft passed through a gate position and put their lights on, this was when the sky lit up and you realised how many other aircraft were around you. Above, below, ahead, astern, to left and right.

I am pleased to say that the system of timing seemed to work, and the collision record was small, although there was, I believe one such incident. After landing the De-Briefing Technical to establish how the aircraft were standing up, defects, fuel consumption and performance were all dealt with, and then an Operational De-Brief when all aspects of the flight, bombing, radar, navigation, weather, other aircraft attacking, seen or heard, rations and beverages etc.

That last word has brought to mind an incident, which happened on one of our longer flights: We were all on oxygen from start up at night and 10,000 ft by day as our operational altitude might be anywhere from 15-25,000 ft. It was usual for one of the gunners to be in charge of the hot drink thermos flasks these were a large variety and usually stowed by the Rest Bed or rear spar area. In the early days we carried two gunners one in the Mid Upper in charge of the 20 mm cannons and tail-end Charlie in charge of his .5” Brownings. Later the Mid Upper was removed and the top fuselage faired over. Oxygen economisers and supply hoses were strategically placed in the fuselage to allow crew members to move back and forth with the Elsan being down by the rear door.

Having decided a hot

drink was in order the captain called the gunner and asked him to do the

business, he responded and we waited. He arrived at the spar area and lined up

the paper cups, after filling them he tapped the signaller on the arm to set in

motion the pass along the drink routine. Instead of giving him the hot drink he

grabbed the signallers oxygen tube, and disconnected him from his supply,

picked up a cup of steaming beverage and proceeded to pour it into the Oxygen supply

pipe. At this point we had a Gunner suffering from Anoxia ([Editor’s Note – now

called Hypoxia] Oxygen Shortage) and a signaller at risk of becoming so. The

situation was quickly sorted out but it was a real life demonstration of the

loss of brain and physical ability and facility so often demonstrated in the

decompression chamber.

”Sunray” was the name given to an exercise, which enabled crews to experience

long-range overseas flights, a variation in operating conditions, and the

opportunity to carry out some daylight bombing during the winter months when

the weather in the UK was not suitable. The Base Station was RAF Shallufa in

Egypt, located between Fayid and Suez at the southern end of the Bitter Lakes.

The whole squadron would fly out usually with five minutes between departures

and our detachment left base on 3rd March 1953 flying first to Idris, Tripoli.

The original name of this station was Castle Benito named after its builder and

founder Benito Mussolini, it was renamed Idris after the King of Libya.

The first leg took just under eight hours and after a night stop we took off again for Shallufa this leg being just over five hours. Our detachment arrived back at Hemswell on 1st April, we had flown sixteen sorties plus the four legs out and back, just over 83 hours. During the detachment we carried out regular visual and radar bombing, gunnery air to ground exercises, and simulated gunnery during fighter affiliation, when the aircraft is flown fairly violently in corkscrew manoeuvres in an attempt to stop the fighter getting hits with his cine film gun cameras.

We also had a fighter affiliation exercise called “New Moon” with the Turkish Air Force. This involved a transit to Nicosia and back with a couple of days in Cyprus. During our exercise we had a couple of frights, we were briefed to take as many photos as possible whilst on this sortie, but all was to be destroyed in the event of a forced landing.

The terrain was very mountainous but we were not briefed to expect any unusual weather phenomena, as it turned out we were not the only crew to suffer this terrifying experience. We were cruising at 15,000 ft when the speed started falling, power was increased and the RPM put up to 2650 max cruise, speed was still falling and the aircraft starting to descend. The throttles were placed at the TO gate and RPM up to 2850 the maximum apart for TO. We were still in trouble so RPM was selected to 3000 and the throttles were pushed through the gate for what it was worth. The mountains seemed to be getting closer and closer, Graham looked grim faced, we had all the power available and the drift down continued at the minimum speed he dared to fly at. I think we all had visions of curtains and our lives flashing through the mind, surely it could only be a matter of time. We had parachutes of course but it did not enter into the sequence to think of baling out. The fight for speed and stability went on and eventually the VSI showed level and the speed started to increase again. Colour returned to the boss’s face and the mountains slid by just under the aircraft. Progressively we regained our cruising altitude and speed and the power was reset for a normal cruise.

During debriefing we would not leave it alone, but it did not seem we were believed. Of course a lot is known now about standing waves, but at that time they were generally unheard of. We had settled down after that when the i/c burst into life “mid upper to pilot – attack attack from the port beam” when interrogated he had seen two Turkish fighters in a tight turn coming for us, white puffs were visible and he was convinced we were being shot at. It eventually turned out to be condensation or vapour coming off their wings in the tight turns. Sanity returned as they came into formation prior to a session of real fighter affiliation and evasive action.

Enough excitement for one day we returned to Nicosia and after a break, set off back to Shallufa. At Shallufa I was rostered as Orderly Sgt, this was in fact the first time I had fallen for the duty in the 22 months since I graduated, and it was just my luck to discover I had a special duty. The Orderly Sgt had to raise the RAF Ensign just after dawn and lower it at dusk, accompanied by the Orderly Officer, who took the salute during the raising and lowering sequence. The drill was to fold the flag carefully, so that it could be broken out after hoisting (no training ever given for this one), a whistle blown would bring all traffic to a halt, and a further blast would indicate the ceremony was over. For my first effort, Queen Mary had passed away at the age of 85, and I was on duty on either the 24th or 25th March the day the ensign had to be flown at half mast – up to the top of the pole, break it out, pause, and lower to half-mast, and a reverse later in the day. I am pleased to say it went off without a hitch, another new experience gained.

Whilst we were away

on that trip, a Lincoln and its crew were lost in Germany. Most people will

have heard of Checkpoint Charlie the famous entry into East Berlin from the West,

but the Berlin Air Corridors may not ring such a familiar note. In order to get

to RAF Gatow, Berlin, in the British Sector aircraft had to fly through the

tightly controlled Air Corridors, in this instance from Hamburg. On this

occasion a Lincoln was transiting the corridor, and maybe it strayed the truth

was never very clear, but instead of the usual buzzing by Russian MiG fighters,

it was attacked and as a result six of the seven crew members and the aircraft

were lost.

Throughout the tour all engineers were checked annually by the Wing Engineer

Leader, it was called a Basic Efficiency Examination and took place in two

parts. The ground examination was a mixture of Oral questions, and questions

requiring a sketch or diagram to answer, and a more practical walk around the

aircraft and equipment. The flying test was simply an observation by the

examiner of one’s performance when flying the aircraft, straight and level,

turns onto a specified heading, climbing and descending turns, the engagement

and operation of the autopilot, and being able to trim the aircraft. Flying the

aircraft was routine for most of us, we had to fly the Link Trainer to a

reasonable level of proficiency and with only one aircraft per squadron fitted

with dual controls had to be adept at swift seat changing as there were not too

many pilots who wished to be in the seat for the total duration of our flights.

At the end of my tour I had logged 155 hours at the controls and over 70 hours

in the D4 Link trainer.

On 7th August 1953 our crew captained by Graham Smith were called out for an

Air Sea Rescue Search over the Atlantic. We were trying to find an American

B36, which had gone down. We departed Hemswell at 0610 in RA713 in my logbook

only as ‘B’ and set course for RAF Aldergrove flight time 1 hr 20

mins, of which I flew the machine for an hour. After filling up with fuel,

having a meal, and briefing we departed for the search area at 1045, on arrival

we went down very low as the weather was almost on the sea, all of the crew

were on lookout with the exception of the plotter and Graham who whilst looking

when he could was concentrating on his low flying.

The sea was very

rough and the chance of survival minimal. It was well into the afternoon about

1515 when suddenly Norman Peach the Signaller who was in the nose called out

“We have just passed over a dinghy” the captain leapt into action like a big

spring being released: he gave an immediate instruction to the Navigator “Time

me 30 seconds, then 45˚ turn right for one minute, then a rate one turn left

onto reciprocal. All eyes out after the turn, signaller make a report to

HQ. Now eyes down”, and there it was a large grey dinghy, with what looked like

a body on it, there and gone if a split second. We fixed our position and climbed,

set up a holding pattern at endurance settings and became a control centre.

Eventually a ship came on scene picked up the dinghy and took over as

controller. At this point we set off back towards Ireland flying at our most

economical speed, Aldergrove was not available due to weather and we made for

Belfast Nutts Corner arriving there after 12.40 flying time, a quarter of it

being flown by myself. With a fuel load of 2850 gallons, we had probably pushed

prudence to the limit and attained the maximum that could be squeezed out of

that fuel load. I had only managed 12.55 on 3650 gallons out in Arizona!

Back on 97 Squadron the routine carried on, we worked on the Lawrence Minot

Trophy Competition, completed exercise Momentum, had a night at Buckeburg and

even did some formation flying for the Battle of Britain Flypast.

About this time we had a new Flight Commander Flt Lt Brindley F Ryan, he introduced a number of new ideas to our operating techniques, regular crew checks, and pre-nomination of various speeds, which had to be called during the take off. This is, of course, normal routine now but was an innovation at that time. Early in 1954 I note that Graham Smith is not featuring in my Logbook I suspect he also went to RAF Jurby on an OCTU Course. In March I flew with seven different captains, Flt Lts Williams and McGillvray, Master Pilot Harris, Fg Off Lambert, Sqn Ldr JJ Barr, Capt Hamilton USAF, and FS Ted Szuwalski.

The last named was to become a new running mate we flew a Lincoln five times in March and April, and during that time were selected to be one of four crews, two from 97 Squadron and two from 83 Squadron who would be flying the Lancasters which had been delivered for film work on The Dambusters. Three of the four airframes had been modified at Hemswell to enable them to carry what was supposed to represent the Bouncing Bomb used by 617 Squadron on the Dams raids. For our familiarisation we had a look at the Pilots Notes, examined the aircraft inside and out, ran the checks a couple of times and made sure we could start the engines. I had to get my First Line Servicing Certificate signed up to say I was competent to do the necessary when away from base. I now had Lincoln II, Tiger Moth, and Lancaster VII signed off.

The other pilots were Flt Lt Ken Souter, Fg Off Dickie Lambert, FS Joe Kmiecek, and I flew with them all during the six months we spent on this task. For our first flight, Ted and I flew to RAF Lossiemouth in NX782, stayed for lunch and then brought it home, nearly five hours flying and I had an hour on the pole. That was the sum total of our training. Three days later we were on Low Level Formation practice, followed by low-level runs over the dam on Derwentwater, we simulated the V Landing Lamps under the fuselage casting beams meeting on the water to establish flight at 60 ft. Next was formation runs over both Derwentwater and then Lake Windermere. After more formation flying and a stream landing at RAF Scampton the operation really got started.

There are many sequences in the film where the Lancasters were carefully positioned in the foreground, and the Lincolns from Scampton or Hemswell are in the background. The number of propeller blades three on the Lancs and four on the Lincs was the major give away, but they made a good background for the purposes of the film. Each time we flew there was filming activity of some sort, The Take Off, flying in formation, low flying, landings. The film crews travelled around to be at the various venues, there was an Oxford PH462 flown by Flt Lt Caldwell used for filming from, also a Wellington MF628 flown by Flt Lt Birch, and a Varsity WJ920 with the right seat and windscreen removed which was flown by Flt Lt Scowan, this aircraft had a tripod fitted instead of the right hand seat and was used for a lot of the air to air shots, there was also another Varsity WJ912 flown by Plt Off Mathieson used to facilitate the movement and filming.

We simulated a delivery scene at Scampton, with a low formation flypast and circuit, it was on this occasion that I learnt I had to be a mind reader as well, Ted was busy pumping the throttles as we climbed away between the hangars, but we were not holding station, I reminded Ted we only had about 2400 RPM and got the answer “WHY YOU NOT GIVEN ME MORE?” I set 2850 and we got back onto station. Ted spoke in a broken mid-European version of English as did most of the Polish and Czechoslovakian pilots and Air Traffic Controllers, it was generally understandable, but got more difficult as the adrenalin content rose.

One Sunday morning we were positioned at Syerston. The Lancasters were positioned in a semi circle around a dispersal pan, the film unit was in the centre and a refreshment van was supplying bacon sandwiches for breakfast. It was normal with the Lincoln and Lancaster to cool the brake sacks on arrival at a parking position by applying the brakes and releasing them a couple of times, and finally release the brakes when given a signal by the ground crew. We had no ground crew or chocks at this point and with the aircraft seemingly safe we left it standing with the long access ladder up through the Nose Hatch.

A scream from Ted told me we had a problem, and on looking at the bird I could see it was creeping forward. I ran to it and tried to climb the ladder but as I went up it started to come through the vertical and I had to abandon that method of gaining access to the brakes. I really ran to the rear door, threw myself in and clambered through the fuselage, into the cockpit, and grabbed the brake lever which was on the Control Hand Wheel, fortunately we still had some pneumatic pressure and the beast stopped just short of the filming equipment – no damage done but another of those “I learnt about flying from that” situations.

Most flying was done in formation, and we spent one session doing wheeler landings and rolling off them, this was not a normal activity on Lincolns! RAF Kirton Lindsey was a grass airfield about five miles north of Hemswell, it was used at that time for some form of training (probably pilot) we did a fair amount of activity there, the most exciting was our first visit. We were briefed to fly a circuit in formation and then land still in formation. The landing was not a problem in itself we were all down and rolling towards the north west corner in a neat gaggle, the grass was wet and retardation not particularly good. All aircraft were by now trying hard to stop before the perimeter was reached, but the Kirton Lindsey ground crew had picked out an aircraft each and were trying to marshal them to the positions required by the film crew – we were busy trying to stop without colliding with each other as the space available became narrower and the aeroplanes closer, I am pleased to say all ended well and the aircraft were later repositioned to suit the filming. After the formation landing we were tasked with a formation take off, not too much of a problem with this, but a considerable heave was experienced as we crossed the runways.

A more pleasurable experience was flying in formation around Lincoln Cathedral, an exercise not normally permitted. RAF Silloth was an airfield up by Carlisle, which had a Maintenance Unit on it. At the time of making the film the MU were engaged in breaking up Lancasters, and whenever we needed a part this is where it came from, taken off one of the aeroplanes in the graveyard. This was a very sad sight, engines cut off and lying on the ground, instruments smashed with a hammer, and the airframes reduced to aluminium waste for recycling as saucepans etc!

Oulston, and Biggin Hill were other airfields we visited, and the latter was for a Battle of Britain display. After the BoB display in mid September, we did not fly the Lancs any more, they disappeared from Hemswell as mysteriously as they arrived. The cinema in Lincoln was a daily meeting place for the aircrews, film stars, producer, director, lighting and other cameramen, continuity girls etc. etc. We gathered after the normal show, and viewed the Rushes which were the sequences filmed on the previous day. We also used other cinemas when we were working away from Lincoln.

In summary I flew

about 60 hours in the Lancaster whilst making the film, over 62 sorties, in all

four aircraft and with all four captains.

During the film making, PO Ken Marwood arrived towards the end of May in a

Meteor VII WA592, and took me for a 45 minute spin, some aerobatics and a short

period of hands on, the next time I saw him he was a Wg Cdr, and President of a

Biggin Hill OASC Board.

Looking at my Logbook after this milestone I see the name FS Ryba, shortly

after he arrived we had an inspection. The CO – Sqn Ldr Grant GD Nav

stopped in front of Ryba, looked him up and down and asked, “Where

do I know you from” the reply was of course in broken English and sounded like

“You dropped zee bomb in mee Elsan”. They had met at a board of enquiry, this

Navigator Squadron Commander had actually released a visual bomb, which had

penetrated another Lincoln flying below it.

The squadron was by now concentrating on navigator training, which finally resulted in 97 Squadron and 83 Squadron becoming Arrow and Antler Squadrons and losing their numbers in Jan 1956. My last flight in a Lincoln was on 18th February 1955 with Brindley F Ryan, and I had 1369 hours on type, a number familiar to most officers as the dreaded Annual Confidential Report. I did in fact fly Lancaster PA474 The City of Lincoln later in my career.

Chapter Two – The Handley Page Hastings of Transport Command (TC)

In Bomber Command each individual had their name on a board run by the Flight Commander, and as the tour progressed the individuals Colour Code altered until on reaching the final colour it was time to be posted. My final colour must have expired in March 1955 for a posting to 242 OCU, RAF Dishforth was handed to me. I was delighted, it was for a conversion onto the Hastings, and that meant some overseas travel and a new challenge.

During my time at Hemswell I had changed the Ariel Red Hunter for a BSA 500 Twin, and then for a Matchless G9 500 twin, which was a much smoother runner and nearly new. It also had a rack and a couple of panniers, but still not enough capacity to move all my personal effects and kit in a single run. The OCU ran from March until July, four months compared to three for the Lincoln conversion. The ground school was quite long and covered a wider spectrum, and when the time to fly came we had already formed ourselves into crews, pilot, navigator, signaller, engineer, and quartermaster. (At this time they did not wear a brevet and were suppliers).

My captain this time was Flt Lt Des Divers. At the end of the ground phase there was a series of tests or exams, and when the results were published I could not believe my lowly placing in the Order of Merit. This led me to do some snooping one lunchtime when I found the offices deserted. Whilst in the Wing Engineers Office I located the test results, and they did not reflect the order of merit, which had been published, which was based on rank and experience, so as a Sgt with a single tour I was at the bottom. Clearly I had joined a system, which supported the old boy net from start to finish. Useful, but not in my interest at this stage, so I decided to rock the boat. After a number of interviews it was finally agreed that the places could be revised to indicate the order of placing to match the test results.

The Categorisation System in TC was much more formal with local examiners and the famous TC Examining Unit, which also had examiners for each trade. It was normal to leave the OCU with a “D” Category, which indicated inexperience or a poor result, and it limited one’s ability to carrying Freight or Troops! With a certain amount of effort and determination I managed to get “C” marks and assessments in all aspects of the course and left with a “D” recommended “C” which could be upgraded to “C” after I had sufficient experience on type.

There were minimum hours as well as test marks to be achieved. Flying started in early May and there were 31 exercises to complete, some of them were solo for the crew, the first after about seven hours. But as engineer I was solo before that, and my night flying check did not materialise at all, which can be read back that the Staff pilot instructors must have been happy with my performance. With all but the final exercise complete we set forth on the Route Training Flight, Dishforth to RAF Lyneham, which was the major Hastings base. Here the aircraft would be loaded and we would clear HM Customs. For the crews a night stop at Clyffe Pypard, a Transit Camp on the top of a Hill near Wootton Bassett. Service Transport was provided once we had been to Operations and booked the Meteorological Data for the route, and discussed the technical state of the aircraft and what fuel load was required. Once again hutted accommodation and stoves to manage, after getting spruced up and having a meal we walked down the hill to the “local” famous for its scrumpy cider and some of the locals who partook of it- they could be difficult to understand early in the evening, but by closing time even more so. The climb back up the hill was exhausting, and helped to ensure a good nights sleep.

Transport days started early, and breakfast, transport and briefing had all got to be fitted in before a typical 0600 departure. On this our trainer the routine was different and we arrived at 1100 and departed exactly 12 hours later for Gibraltar, a similar routine at Gibraltar and departure for Idris again after a 12 hour stopover. On all trainers the Staff or Screen Crew normally worked one leg and the leg to Fayid was theirs. Next stop was Luqa, then Lyneham and finally back to Dishforth. At each stop we were given a conducted tour of all of the facilities, messes, shops, ATC, Operations, where to order rations and early calls etc etc. At Lyneham it was invariably all baggage to be removed from the aircraft and a march through the Customs shed. In those early days it was a corrugated iron building and the severity of the process often depended on how good or bad Swindon Town had performed in their last match.

Each leg was debriefed both as a crew and as individuals. We arrived back at Dishforth on 6th July, and on the 7th, we flew our final exercise bringing our hours for the course to almost 106. At some stage I had asked about parachutes, having carried or worn one during my Lincoln tour, I got a strange look and was referred to a Transport Manual I believe it was called The Transport Force Supplement. On poring over this magic document which turned out to be a real bible full of pearls of wisdom, I discovered that they would be carried if the King or Queen were on board, or if engaged on Supply Dropping or Towing. Two days later I was at my new unit 24 (Commonwealth) Squadron at RAF Abingdon and in those days it was in Berkshire. Our crew had been split up and I seem to think I was alone joining the Squadron.

The routes were varied, but the bread and butter was Australia, the Near and Far East. On the OCU all the Hastings were Mk Is, but my first flight at Abingdon after two weeks leave, was in a Mk IV, captained by FO Bob Reynolds, who became my next-door neighbour some 10 years later – it was an airtest, and my acceptance flight, a good shake down. The Mk IV was similar to a Mk II but fitted out for Royal/VIP Flying, similar to the Mk II they had a much-modified horizontal stabiliser and were considerably easier to land.

A few days later I drew the short straw for a continuation training sortie with three captains FO Barrel, Flt Lt Pearson and the Squadron Commander Sqn Ldr Kerr there were no problems, and I was programmed the next afternoon to fly with Flt Lt John Connolly – he was a Wing Pilot Examiner.

We flew a few circuits of varying sorts, and he declared he needed to practise some Short Landings. A technique where the pilot calls for a progressive reduction of power on the approach whilst he gets the airspeed down to a minimum figure determined by the weight and just above the stalling speed, and then he calls for power increases until he has the aircraft settled at low speed and rate of descent, after crossing the runway threshold he would call for a Cut, the power was instantly removed and the aircraft sat firmly on the ground. Two of these approaches had been carried out, and we settled down to a third, power calls were normal and the aircraft was settled with plenty of power, I thought I heard Cut, repeated it and closed the throttles, a voice came back No – Standby to Cut (this standby call was a non-standard one) there was a crunch and a voice said Too Late. It was a heavy landing just short of the pavement. The right throttles went fully open and the aircraft came to rest after doing a curve across the airfield. Cut and Abandon was the next call and the Navigator, Signaller, and Copilot were hotfooting it down the fuselage to the rear door. John and I killed the fuel and electrics and made our way to the rear door, at which point I decided I ought to disconnect the batteries. I raced back up to the cockpit, up with the floor hatch, down the hole in the dark to the batteries at the back of the bay, trying to visualise in the dark which pair of leads to remove first. (With the +VE side of the batteries connected to the Airframe, if the +VE Links were half removed and allowed to touch the structure there would be a big flash, as they made a short circuit, and possibly even an explosion as the batteries give off hydrogen whilst being charged.)

After what seemed a lifetime I had done the job, and joined the others who were well clear of the wreck. The front spar on the starboard wing had sheared, and the wing rotated around the rear spar axis. Both Nos 3 and 4 propellers had feathered due to the extra loading in the control runs, and the starboard flaps were like plough blades digging in the grass, fuel was also leaking from the ruptured wing, and the fire service were now in attendance, much to our amusement complete with a short wooden ladder!

After a short inquisition we were transferred to the Medical Centre for an examination and tests, and finally released for lunch. After lunch John and I were separated and asked to write a comprehensive report of events leading up to the accident. Whilst we were waiting to hand them in to the CO, we read each other’s report and there were no significant differences. Later that same day our helmets and masks were tested and mine was declared to have an intermittent fault. That could well have been a contributory factor and I was later told that I should feel 5% responsible. Much more significant was the fact that there was not any Board of Inquiry, and by tea time we were told the fracture site revealed considerable corrosion and fatigue and it was going to fail sooner or later anyway.

The other side of

this story was the fact that on it was painted in large letters Johns No Two

very shortly after the event. I am not sure of the time scale, but John had

previously been inbound to the UK one night when the country was fogged out and

no airfields were accepting inbounds. In the pattern at Abingdon John saw a

clearance, they flew a circuit, saw the lights clearly and landed. It was

rather unfortunate that the landing was on a solid but thin layer of cloud with

the lights blazing through it. The aircraft of course stalled and dropped

firmly onto the runway and suffered a similar fate to the event described.

The Parachute Training School made good use of both of the fuselages for the

parachutists to train in saving wear and tear on the line aircraft.

Two days after the heavy landing, I was on route, almost the same one that we did for the trainer: Lyneham – Luqa – Fayid – Khormaksar – Fayid – Luqa – Lyneham. In the last week of August I set off on a trip to Australia, the pilot was Flt Lt Keith Isaacs, Royal Australian Air Force. There was no formal crewing system on 24 Squadron. The various tasks were listed on a board which was passed around the sections, individuals made bids for trips they likes the look of and for those already away on route their leave bids were considered and they were slotted into suitable ones. Of course there were limitations to the allocations and Categorisation had to be considered when a task was identified as VIP at one end of the scale and Freighter at the other.

I enjoyed flying with Keith, and his warped sense of humour, and endeavoured to fly with him whenever it was feasible to do so. He was a smallish gentleman, and the Mk I Hastings was a bit of a beast at the final point on the landing. Keith could just not muster enough strength to heave back on the control column sufficiently hard to get the tail to lower, and at the critical moment he would issue a rallying call to the other pilot to heave with him. I used the term other pilot deliberately, for they were generally 2nd pilots – not qualified on type with an OCU course but just instructed locally where the various controls were. On other occasions a Co Captain flew in the RH Seat particularly if it was a VIP Flight.

A month after arriving at Abingdon I set off on my first long route, it took 17 days to complete, and we had a day’s rest in Australia at the half way point and in Singapore. The route makes interesting reading as names of places change and various countries became politically opposed to the military and landing became more difficult. This one was via Lyneham for customs and loading – Idris for a night stop, 12.30 actually on the ground, and out of that was taken putting the aeroplane to bed, a debrief with the Met Office, after flight and before flight meals, a generous helping of Marco’s Brandy Sours which seemed to be the recognised thing to drink, and of course some shut-eye.

The early call arrived with a cup of tea and the next day started usually before the sun came up. El Adem next for what was called a “Flag Stop” where the aircraft was only on the ground for 75 minutes. The next point of landing was in Iraq at Habbaniya up on the Plateau Airfield. There followed a coach ride down to the main camp where the desert had been transformed by irrigation and the roads were lined with palms and flowers. Up on the plateau was a forlorn Hastings, it had arrived there with a serious problem, and currently had 3 engines and a bulkhead, and I believe a fixed landing gear. All arriving crews were invited to fly it down to the main station – this request was generally declined, but eventually some adventurous souls did just that, it was repaired and returned to service. The staging posts as they were generally called were in the main large enough to sustain the normal mess system, where the crews split off to their respective messes, but at some stations there was an all ranks Transit Mess.

From here we set off again 12 hrs 30 mins later for Mauripur in Pakistan. Here the evidence of Imperial England was clearly visible with lots of officials, customs, immigration, papers and rubber stamps in evidence. The drive from the landing site to the accommodation was past miles of Shanty Town made from any scrap material that could be found and the odours in the air rather foul.

Our next stop was at Negombo in Ceylon, both of which have changed the airfield name more than once. A very different atmosphere and climate here, English beer, and a sample of the local curry, which was particularly, hot, and made its presence known again the following day when it passed on! Yet another new experience!

Next onto a rest stop at RAF Changi on Singapore Island. The airfield was at one end of the village and the All Ranks transit mess at the other. Being an overseas station it had all the usual messes and facilities including a golf course and a hospital. It was possible to walk from venue to venue but short cuts were not advised as the monsoon drains were hard and deep and took many prisoners as they staggered back to their resting place. Talking of prisoners, the now famous Changi Gaol was just past the airfield on the road to Singapore City, and it was here that many of the aircrew took their Flying Logbooks to have them bound into volumes.

Shopping, bartering, eating and drinking in the village were mandatory, and most crewmembers would have vast shopping lists, for presents etc. Cameras, Electrical Goods, Toys, Cycles, Tyres, Car Accessories, and even small TV sets for use from mains or 12 volt supplies – there was nothing which could not be obtained cheaper than in the UK. Suits and shirts made to order almost overnight, also ladies dresses made from patterns, or just to a size in a local design. Khaki Drill uniforms were also made to measure. At this time we were still wearing the original pattern and the overnight laundry service available in the messes brought the KD back looking like new and stiffly starched.

Changi Creek Transit Mess was exceptionally well laid out, with chalets, bar, dining rooms, lounge, reception and it looked out onto the creek over extensive gardens filled with colourful shrubs and lawns, and of course birds and butterflies in many brilliant colours. The boats plied up and down the creek, their engines chugging steadily, and on the other side was a coastal beach, which could be accessed by a short walk, in the distance were islands covered in vegetation. Further along the coast line towards Singapore was Bedo Corner an absolute haven for alfresco dining on the local cuisine prepared in front of your eyes on little stalls along the front. I would add that over the years things have changed and considerable building has now taken place on the reclaimed land at Bedo. The transit mess was also used as the pick up and drop off point for passengers, and there was limited accommodation for them as well.

After 36 hours we were on our way to Darwin almost 10 hours flying, and my first impressions of Australia. At that time before the big storm, Darwin was a shantytown on the north coast, many of the buildings of a temporary nature. It was hot and steamy on arrival and all windows and doors had to be kept closed. After parking the RAAF pushed some steps up to the rear door, and an Agriculture and Fisheries Inspector came on board, walking through the aircraft spraying an insecticide on the way, all unconsumed food, tins, packets, fruit, etc was stripped from our little ship and taken for incineration. The natives definitely seemed hostile, and it transpired that all the bad ones got a posting to Darwin.

Once clear of Customs and Immigration the crew left the engineer to sort the aircraft out, fuel and oil replenishment, hydraulics and pneumatics to be serviced, and last of all, the really nasty job. No – the Elsans (chemical toilets) were done by the Aussies; it was the Tecalemit Filters which had to be changed. This was done when a certain pressure difference built up across the filter giving an indication of its remaining efficiency. The higher the pressure difference, the lower its efficiency, hence the need to replace it. Almost 12” long and 5” diameter the filter was located in the engine nacelles, and it was a messy job involving the removal of the end cap, extracting the filter, inserting a new one and making sure the end cap resealed. Oil drained from the filter case, and had to be prevented from soiling the tarmac. It was hot work and very messy and I seem to think it always needed doing at Darwin.

Once the servicing was complete transport was provided to the billet, and here another shock was in store. All the indoor accommodation was already full so our beds were under the billet, which was on stilts to protect it when the monsoon floods were taking place. At least it was air-conditioned by nature although it seemed very hot and sticky inside the mosquito net. The showers and toilet facilities were also primitive and I can remember looking up at the back of the toilet door and seeing a line of toads sitting on the bracing bar observing the action. More of this, when turning to operate the flush there were more of them with their heads sticking out of the unused overflow orifice and where an alternative handle position was located. Eventually I get to the bar and discover they had some weird rules about when one could drink, and when at last the beer came it was so cold it was almost freezing, and it was in a tiny glass. Oh well the food was excellent, steaks anytime and generally good tucker – no wonder they were all big strong healthy boys.

The flight to Edinburgh Field, a military one just North of Adelaide, took 7 hours and this was more like normal accommodation, and the airfield a hive of activity. It was a ministry research and development base, and one of the projects was a Meteor being flown by ground control whilst the pilot sat and watched! On the rest day we managed a very quick visit to town, saw the shops, the gardens and zoo and the Murray River. The architecture was a mixture of early colonial wooden buildings and some very large brick structures with a very Victorian feel to it.

The return flight followed a similar pattern, the trip taking 17 days, and would be followed by a stand-down or Route Grant, as it was known. My next trip was a short one to Malta (Luqa) and Cyprus (Nicosia). The impression of Malta was one of brilliance, white rock in all directions, and buildings made from stone and similarly painted. The taxis and busses were well used and felt rather rickety, and all carried a model of the Virgin Mary in the proximity of the driver. The roads were poor, but the shops quite interesting, and I managed to purchase some 78 RPM records, which had long since been dropped in the UK. The transit messes were well organised and all servicing carried out by the Staging Post Staff. There were of course beaches and restaurants, but there was not time on this stop to investigate them.

My next long trip was my first Christmas out of the country. It was a freighter to Changi and we left Lyneham after being loaded with mattresses and oil stoves! The mattresses were easy to explain; as many beds down route still had old hair-filled ones and these were Dunlopillo. The oil stoves were for some of the near and middle east stations where it can get very cold at night in the winter months. We arrived at Changi on December 23rd. having followed the standard route, and did not leave until the 27th. The Trunk Route was closed down for the break. We were treated extremely well by the staff at Changi, and with a break that long many of us found friends on base to visit. At Mauripur on the way back we had an engine change, a chance to get stuck in and learn a bit more about the aeroplane and this added another two days to the schedule, and required an airtest before we set off again.

Further trips added Bahrain, Gibraltar and Car Nicobar to my overseas tally; the last one was not a routine stop for the larger transport aircraft, but the Vallettas of the Far East Communication squadron were a regular callers. During the period between January and March the EOKA problems took a turn for the worse and tensions heightened in Cyprus, I was involved with three detachments there, and times were not pleasant. On base at RAF Nicosia it was cold and muddy, and accommodation was at a premium we were even sleeping on the billiard tables in the Sgts Mess, or in the partially completed Air Traffic Control Centre.

As things got more organised some of the crews were shipped out to safe hotels, and the main one was The Castle Dome located up on the north coast at Kyrenia. The journey across the island was very tense, especially on the mountain roads where an ambush might be expected. We were all armed with Smith and Wesson revolvers, or side arms as the official designation went, and the RAF Regiment, travelling in convoy by Land Rover, escorted the crew coach. The hotel was quite up market and had many elderly residents staying for the winter season. The furniture was hand made and large with some excellent built in door mirrors, and this leads us to another event.

Weapons were supposed

to be loaded when going out into the town and kept unloaded in the hotel. Bugs

Bunny, a Sgt Quartermaster, was alone in his room playing scenes from a Western

with himself by practising being quick on the draw, and aiming at the door

mirror reflection of himself. You guessed there was a loud bang in the hotel

followed by the sound of breaking glass; he had loosed one off accidentally at

the reflection of himself in the mirror. The hotel was indeed a hive of

activity whilst both the military commander, and the staff established that we

were not under attack, where the noise emanated from, and what or where was the

broken glass. Bunny appeared from his room during the hubbub, and offered

himself as the sacrificial lamb. Needless to say there was some tightening up

of the gun regulations, an armoury was established, and a duty roster created

to control the guns and ammunition.

The next significant event was a flight with the Squadron Commander Sqn Ldr

Bolt RNZAF to Fiumicino, we routed via RAF Turnhouse, Dijon and Istres. It was

a support flight for 43 Squadron Hunters who were going to display at MAF 56.

This was a major event staged to celebrate the opening of this new NATO

Airfield. 43 Squadron were at that time the Royal Air Force Aerobatic Team with

their black Hawker Hunters long before the Red Arrows and the permanent Central

Flying School involvement.

Operation Buffalo was the next challenge, and Operation Grapple followed this without a break apart from the flight from South Australia to Christmas Island. Departing Abingdon on 3rd August. We arrived back there on 11th November. The year was 1956 and the exercises were integral with the Atomic Bomb Trials in Australia and the Pacific. We carried two Captains, Sqn Ldr Bolt and FO Bob Reynolds who was an ex-NCO pilot, and later became my neighbour when I moved to Lechlade on Thames for a tour some 10 years later.

The flight followed the standard pattern up before dawn, or the crack of sparrows, as it was known, breakfast and away as the daylight arrived, landing in time for tea, a wash and brush up, then dinner, bar and bed was the standard order of the day. The route followed was also standard until we left Changi and had to call at Kemayoran Airport in Djakarta on this occasion and after a refuelling stop made our way to Darwin. The next day we arrived at RAAF Edinburgh Field, and settled ourselves in for an 18 day stopover. During that time we flew a variety of sorties between Pearce on the West Coast, Maralinga, inland and North of Adelaide, and Edinburgh. We also spent a few days at Maralinga with an item known as a Heavy Beam fitted to the underside of the aircraft. This was as its name implies, designed for heavy loads, which could of course be airdropped. On this occasion, scientists from the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment, wired up the aeroplane, to enable the transfer of data to the equipment and monitors fitted into the fuselage, from the sensors and external gear fitted to the Heavy Beam.