Many thanks to George Roberts for this story. George is also the chairman of Tayside branch of the Aircrew Association. Following the passing of the Association’s archivist he took custody of a large quantity of material including a number of stories about wartime flight engineers.

Introduction

What will tomorrow bring?

I had always fancied putting in print about my exploits during World War 2, and it took me 50 years to find the time. You know the questions you get, “Where did you meet Granny?” and, “What did you do during the War Grandad?”, and I never could give a satisfactory answer.

This is not the complete story, it is only the bits I can remember and it is possible the actual occurrences happened at different times to what I state. The important point is, I can assure you, that they did happen and it is not my imagination running wild. I was a teenager when war came and fully believed, like most people, it would be over in a matter of months and that I would never see any action. I am not going into any details of the war years, only how it affected me.

I was a railway clerk and played at soldiers in the Home Guard, although it helped when it came to the real thing. We lived at the South end of a railway tunnel and late one night, watching and hearing Rosyth taking a beating, even at that distance., an enemy aircraft following a train in, dropped his bombs on the tunnel, no doubt thinking it had entered a station. They landed only yards away from one of the ventilation shafts.

The War dragged on. Dunkirk came and it started to come home to us we were all in it. The bombing of our Cities, the casualties, and more depressing news nearly every day. Relatives and friends gone, some prisoners of war, and mates getting their call-up papers, it was going to be a long and arduous affair.

The Battle of Britain made up my mind for me.

I was volunteering to be a pilot.

Chapter one

It was July 1942. I was two months off my 20th birthday and on my way to Padgate to join the R.A.F. Prior to this, I had spent three days of medicals through in Edinburgh and pronounced fit for aircrew, but too short in the legs to be a pilot.

Like any other young man, I did not like the confinement of the kitting out and basic training, otherwise, I accepted it and the company was good.

Ten days later, heaven beckoned off to Blackpool. I can always vividly remember that first day marching down the Golden Mile through the holiday crowds to our billets on the South shore. And that night out on the town, all new to me, never having been to an English seaside town before, I liked it.

Not too keen the following morning, up at six and out running in shorts and vest on Blackpool sands, but gradually accepted service life. Drilling and marching to and fro on the promenade to the delight of the holiday crowds. Quite embarrassing to lead the parade through the streets, all 5ft 41/2 ins of me. Out at nights looking for crumpet and if you struck it lucky, there were no more generous lasses than the Lancashire mill girls. At the Tower circus and walking back like a zombie, having had my jags that day. I did not smoke or drink then and life came easy. Pleasant memories of these days, and then it came to the passing out parade.

It was on to Squires Gate for my Flight Mechanics course and a move of billets further down the South shore. Right opposite the Rendevous cinema, run by two old dearies, who did their bit to starve or poison us, nine Scots and nine English and an Irish Corporal, with I.R.A. sympathies, in charge ! But still enjoyed the life.

Blackpool that winter was a cold and stormy place. It was an experience to brave walking along the promenade battling against the wind and the spray from the waves. Passing out time again. I made A.C.1 on my marks and home at last for a spot of leave.

Posted to Insworth Lane, Gloucester, for my Fitter Engines course. That’s when I began to see what life was all about , and why. Ask any W.A.A.F. who served during the war. Just up the road was the camp for the intake of women, thousands of them, but maybe I am exaggerating. The only N.A.A.F.I. was situated right in the middle of it and we airmen were allowed the facilities. My most pleasant memory of that place is getting lost one night on my way out. Wandering into forbidden territory, kissing a bevy of lovely women hanging out of their billet windows. If I had been caught, the R.A.F. would have castrated me. Passing out time again and posted to an operational squadron (I cannot remember the number) at Elsham Wolds, Lincs.

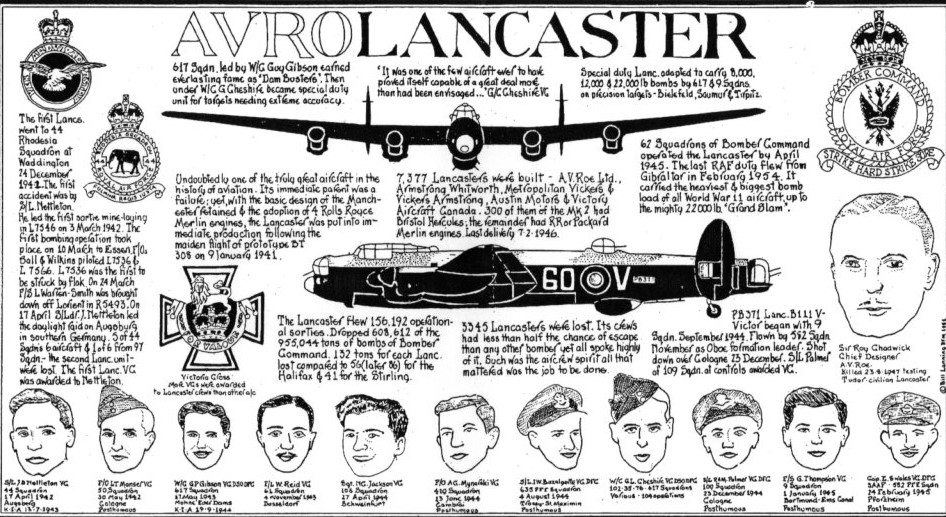

Keeping the Lancasters flying on ops.., mostly engine changes and what a dedicated bunch of chaps those fellows were, great mates. What had I let myself in for? Seeing these aircraft return all shot up, those that did return, and the chop rate as they called it.

They must have been going through the aircrew fast because it was not long before yours truly was on his Flight Engineer’s course, near Birmingham.

Not too much to tell there. It was mostly all study and practical and I just scraped through. It was the middle of December, 1943. It had taken me nearly 18 months to make it. I had my Flight Engineer’s brevet and the rank of Sergeant.

Posted to R.A.F. Stradishall, near Newmarket, Suffolk to join up with the rest of my crew and fate was beginning to show its hand. My crew had done their initial training on Wellingtons and now on converting to Stirlings, they needed me. What a mixture. The Pilot, Sgt. Speirenburg, Dutch; Navigator, Aussie; Second Navigator, Canadian, of German parents; Wireless Op. Londoner of Belgium parents; Mid-Upper-Gunner, Londoner of French parents; Rear Gunner, a true-blood cockney and myself, a Scot.

We gradually became a well trained unit after numerous circuits and landings, cross countries and bullseyes. They were diversionary flights on or near enemy territory to confuse them where the main bomber force was operating, and we got no credit.

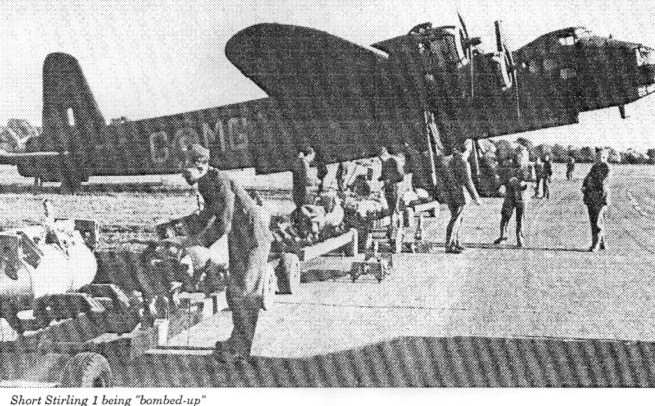

The first bullseye on Stirlings we did as a complete crew was nearly our last.

It was the 14th January, 1944. We took off 18.00 hours and after struggling to 16,000 feet, I think that was the maximum height for Stirlings. We rapidly began to ice-up and to lose height and that was really deadly with these aircraft. Anyway, we got away with it and completed the circuit only to find Stradishall was fog-bound.

Bomber Command were not operational that night, thank goodness, and they diverted us to Graveley, where they had F.I.D.O. Each side of the runway pipes were laid and fuel was set alight to dispel the fog and show you the ground. It was like entering the “Gates of Hell”.

It was on another one of these bullseyes an amusing episode comes to mind. We were rapidly approaching the coast of France when Spiery asked the Aussie Navigator, Bill, when we were due a change of course. The answer came back that he did not care a damn whether we went 10 degrees port or starboard. I went back to see what was wrong and found him slumped over his charts, his oxygen pipe disconnected. Just another example of the risks involved.

It was generally accepted by all of us aircrew, if you survived your initial training, you were halfway there, and personally, I would agree. Flying Stirlings was no picnic. I had seven fuel tanks each wing to juggle about with and if one engine failed, it was curtains.

Christmas Eve, 1943. I went to the flicks in Haverhill. I had been flying that day and must have fallen asleep. Waking up with a start, I mistook the time and rushed out of the cinema to catch the last bus to camp. I was an hour too early.

Also hanging around was a young auburn-haired girl who I chatted up and saw her home to a farm 1/2 mile from the base. That started a romance and a year and a half later, we married. Was it fate at work again?

Chapter two

Oh, happy day, we were off to R.A.F. Waterbeach, near Cambridge, to convert to Lancasters, Mark 2, with Hercules air-cooled engines – super aircraft.

Then on to R.A.F. Witchford, near Ely. Number 115 Squadron, fully operational. More bullseyes and on the 20th February 1944, our first crack at the enemy to Stuttgart.

Beginning to find out the hard way , this flying and bombing was a dicey business.

The scene over the target area will always stick vividly in my mind. Many square miles of flames, the bomb and incendiary bursts, the green, red and yellow target indicators and the bomber force starkly illuminated.

Night fighters everywhere, having a field day, luckily leaving us alone and seeing the unfortunate bombers going down in flames, again the doubts, what had I let myself in for? Great to touch down at home base, get debriefed and a breakfast of eggs bacon and off to kip. Our Squadron lost three aircraft that night.

Three nights later, it was Augsburg’s turn. Not quite so depressing over the target, but just as deadly. No enemy action against us but our wings iced up and we lost height and then we ran into an electric storm. We were also fighting the elements. It was an eerie experience to be caught in an electric storm. You put your hand near the fuselage and the current arced across. That is why there was graphite in the tyres to allow the static electricity to earth, otherwise, you would be electrocuted on touching the ground, or so I was told. Spierenburg, (now Pilot Officer) had applied for us to join the elite, the Pathfinders, and we were accepted. It was off to N.T.U. Warboys for training and conversion to Lancaster 3s, Rolls Royce Merlin engines.

During this time we missed out on the operation to Nuremburg, reckoned to be the blackest night for our bombers, ever. In conversation with crews who had been in the attack, it was thought the Germans must have had prior knowledge of the target, because they ran the gauntlet for miles on the last leg, hanging flares being dropped and the bomb force lit up. The night fighters above knocked hell out of them. Kind of glad we missed that one. The chop rate at this particular time was heavy and 115 Squadron was taking plenty casualties.

Talking about the risks in the Crew Room, a rear gunner (tail-end Charlie), admitted he was nearly at breaking point and later we heard he went L.M.F. (lack of moral fibre). I presume cowardice in the face of the enemy in other words.

I well remember in the transport going out to our aircraft for an air test, the air of gloom over the two gunners and W/Op., which did not affect me. It must have been a premonition of their ultimate deaths. Back to the serious business of bombing.

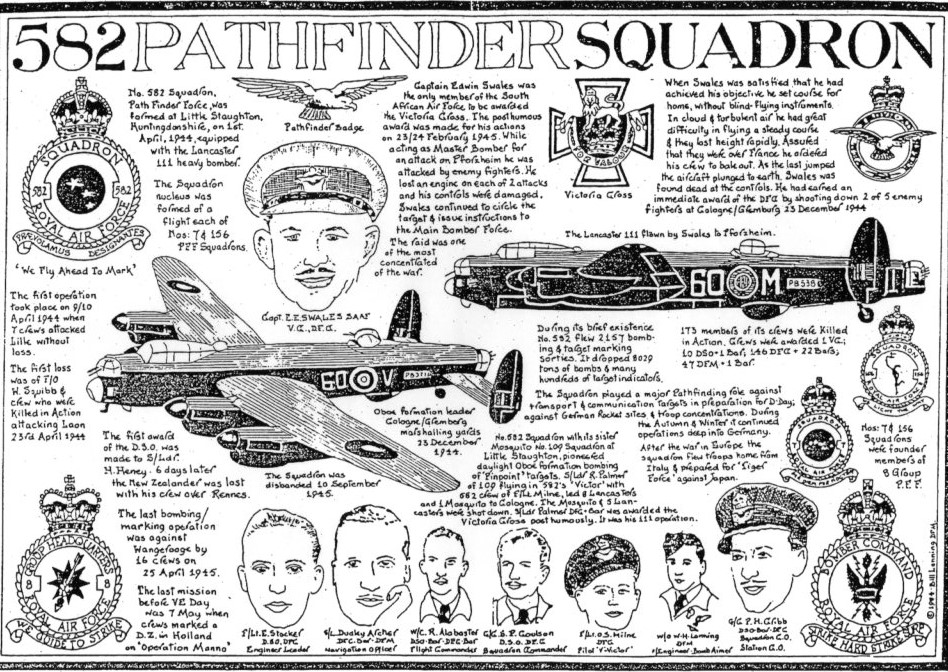

We formed a new 582 Squadron, P.F.F. at Little Staughton, near St. Neots.

To Noisy-le-Sec, Paris, on the 18th April, 1944, as a supporter, that meant backing up the target indicators, as requested. Then came the big one when our luck nearly ran out – Dusseldorf in the ‘happy valley’ the Rhur, on the 22nd April, 1944. It was our first experience of the heavily defended Rhur, being tossed about by the flak and coned by the searchlights, not very pleasant.

On the way back, it happened without any warning. A night fighter on our tail shot us up with cannon fire. I was standing beside the skipper when all hell broke loose. Tracer shells bouncing off the fuselage and wings and one tore a hole inches away from my legs on the starboard side, glancing off the hydraulic gear in the front bomb aimer’s compartment, through the computer box and out the port side and burst, knocking out the port inner engine. Perspex flying everywhere from the canopy, a proper fireworks’ display and the pilot took no evasive action. Minutes later, the fighter was back for the kill, but this time he missed.

He came in again starboard, bow up, but the pilot had regained his composure and threw the Lancaster into a corkscrew dive. When he had levelled out by some miracle, in he came again from the tail. The gunners, both mid upper and rear, had a go and he did not come back. They claimed a kill. And what about myself.

When I kind of got over the first shock, my first reaction was to pull back the throttle on the port engine (and feather the prop), it being on fire. Next thing I knew I was off my feet, scrambling about the canopy during the dive. Luckily, I had only a few bruises to show for this occurrence and the rest of the crew escaped uninjured. We made it back to base on three engine, at a low altitude, nursing the starboard inner engine which was leaking oil.

When we landed, it was just getting light and what a pitiful spectacle our aircraft looked – chunks gouged out of the fuselage and wings. Not a fuel tank unholed and a neat hole through one of the blades of the propellor, port inner. One of our lives gone.

There was a clamp down because of the weather for nearly a fortnight, thank goodness. Because the pilot had not taken evasive action immediately, this caused a rift with the second navigator and he left the crew though he did not last many more operations.

I think it was then Spierenburg married the queen bee, (Senior W.A.A.F. Officer) in Newcastle-on-Tyne and, of course, all the crew were guests. Every opportunity there was a stand down. I was off to Cambridge to see my lady friend – my future wife. She worked and lived there with her sister. Our replacement 2nd Navigator/Radar Op. was an Englishman and he soon slotted in with the crew.

It was 3rd May before our next operation. Montdidier Airport, followed by Nantes Aero Repair factory on the 7th, both without any major incidents.

Again, a break until the 19th May, this time Boulogne, then it was back to the Rhur, Duisburg the target on the 21st. Never did like visiting ‘happy valley’ and they did not disappoint us. You faced a barrage of flak, always the danger of fighter attack, but again we got away with it.

Then on the 22nd May, fate took another turn in my favour. It was normal practice to do an air test on your aircraft during the day prior to ops. That night, Spierenburg was quite emphatic I had lifted the undercarriage on take off before he gave the order and this was supported by the ground N.C.O. flying with us.

What could I say? There was no way of proving right or wrong. He refused to have me fly with them that night to Dortmund, back to the Rhur, and the Flight Engineer Leader took my place. I went with another crew, F/O. Magee, a Canadian, the pilot, and that was the best thing that could have happened to me.

A completely different approach to danger from Spiery, a family man, and if anybody could survive, it was him. My own crew did not come back that night and it was many months later I heard the story. I cannot swear if it is all true, but apparently, near Paris on the outward leg, again they were attacked from the rear by a night fighter and badly shot up and the rear gunner copped it. He would not answer the intercom and they could not get the door of his turret open. Again, the pilot took no evasive action, stating that he had every confidence in the gunners and they stayed airborne.

He pressed on with his bomb load to the target, but they could not maintain height and the aircraft was difficult to handle. The Flight Engineer Leader (my replacement) had had enough and baled out. Spierenburg was eventually forced to give the order to abandon ship and he put it on automatic pilot.

The W/Op and mid upper gunner both landed safely together and the aircraft spiralled, crashed in the same field as they landed and blew up, killing them on the ground. This was reported by members of the Free French Infantry who witnessed the crash.

Chances were, I also would have copped it that night. The F/Engineer, Navigator, Radar Op., were picked up by the Free French and were hidden by prostitutes in Paris until it was liberated. Spierenburg made his way through the underground back to The Hague in Holland, his home town, and so the story goes, killed a relative who was a quisling. The Gestapo captured him and eventually he landed in a camp in Poland, soon to be over-run by the Russians, surviving the war.

That’s how it was related to me and I see no reason to doubt it.

Chapter three

`Mac’ (F/O Magee) and his crew, (one other Scot and four English) accepted me as their engineer (their own being grounded because of air sickness). He was a first-class pilot and had a well-disciplined crew.

We were what was known as a blind crew, most of our bombing being done by radar, so being the engineer, I did any visual bombing, manned the front gun turret and was expected to fly the aircraft straight and level if anything happened to the Skipper. Of course, my main duties were to monitor the engines in flight, try to maintain the most economical boost and revs, to save fuel. I logged the details of all changes and computed our fuel consumption – we never trusted the gauges.

I was always out at our aircraft long before the rest of the crew, doing my pre-flight checks and liaising with the ground crew, who did a magnificent job.

On ops you did your bit of scanning for fighters as well as dropping “Window,” (strips of aluminum foil to confuse the enemies radar) so you were kept busy.

Two nights later, back again to the Ruhr, Aachen this time, backing up the target indicators and three nights later, on the 24th May, Rennes Airdrome.

That one sticks out in my memory because I did the bombing. First time round, I was over -shooting the markers so I asked the pilot to go round again, which he duly obliged. On returning to base, the rear gunner said he was on tenter hooks as there were so many fighters about. The Skipper pointed out there was not much point delivering bombs not to hit the target and that helped my confidence along no end.

There was a wee break then and it was off to Cambridge to see my fiancee. I had it well organised. They were beginning to know me so well in the dormitory in Jesus Lane, that they went out of their way to ensure a bed for me. In the mornings, the civilian workmen on the drome, who lived in Cambridge, knew it was a stand down and they picked me up.

On the nights of 7th and 8th June, I believe we made two short trips after buzz-bomb installations. I can remember the fascinating, but deadly, sight of the red bofor shells coming up at me when you crossed the French coast.

On 14th June, Douai, marking the target, following the Mosquitos. We were attacked by a M.E. 410. It was a lovely clear night and he was spotted by the Mid Upper early in his initial approach. I was down in the front, slinging out “Window” and on being alerted, scrambled up into the front gun turret. Just got there in time to hang on while the aircraft corkscrewed and on levelling up, manned the Brownings.

First attack had been from port bow up, now it was from dead ahead and Mac shouted he had him spotted. I took my timing from the Mid upper (he being more experienced) and opened up when he did and Mac dived. He pressed home his attack , again from behind. The Rear gunner this time giving Mac the countdown to perfection. We all had a go and claimed hits and that is the last we saw of him. No damage to the aircraft. Mac had timed his evasive actions superbly and thanks to the skill of the gunners in judging range and distance, we got away with it again.

Another four trips in the next fortnight, in support of our landings after D-Day and after the buzz-bombs were pretty easy numbers. In between, we had been practicing for daylight operations, formation flying, map reading etc.., and another amusing episode comes to mind.

Bombing practice, and yours truly dropping the smoke bombs. Panic stations below, “Cease bombing and return to base”. I noticed a plug was not in its socket and discreetly said nothing after replacing it. Our first bomb landed in a farmer’s back yard, killing a pig two miles from the target. The second in the middle of a main road, and the third, (I don’t know, God knows where). Thank goodness it was treated as a joke, by our Squadron anyway.

Our first daylight Bocage’ on the 30th June. It was interesting to see two Lancasters go down in front of us, hit by flak and pleased to see the crews bale out.

We were after a German Panzer Division and made our attack at ground level, carrying a full bomb load. The concussion of our bombs blew us up a thousand feet and it gave us the greatest satisfaction when we saw our photographs later; tank crews running in all directions. They had no chance of survival. That photo must be in the annals somewhere, possibly the War Museum.

The first three weeks in July we continued on daylights. Six operations in total, in support of our advance through France. More buzz-bomb bashing, our fighter cover keeping the Luftwaffe away. Then back to nights on the 23rd July, Kiel the target, a tough one, well defended. We got hit by flak on our run in to the target. The W/Op. copped it on his legs, shrapnel splinters, and the Radar Op. went back and patched him up. They were superficial wounds and he stuck to his post.

Glad to get away from this target area and we had no more trouble on our return trip. The crews from the Squadron had been spaced out on this one, banking up the target indicators and we were early back. On leaving debriefing, more of our chaps were landing. We had a ringside view to see a J.U. 88 night fighter follow one of our Lancasters down and strafe him. Cannon shells and tracers bouncing off the runway all round them and they got away with it. They immediately killed the lights and diverted any latecomers and the R.A.F. Regiment opened up. I reckon more of a hazard than the night fighter. If this is what is meant by being back on nights, give me day lights every time.

It was around this time I got to know Joyce. She was the W.A.A.F. who served up the tea and coffee at debriefing. It was something to look forward to. Would I succeed in getting my hand up her service bloomers or get them off, and I never did!

Next night, off to Stuttgart again, with a replacement W/Op. They gave us the minimum fuel against a maximum bomb load. So there was very little to play with against any eventuality. You can be sure I kept the boost and the revs down and logged as accurately as possible and Mac and I nearly fell out over my persistence, but it paid off. We made it home.

The ground crew told us next day that they reckoned we had only five minutes flying time left and Mac shook my hand. Only near thing was the Mid upper reported another Lanc on the same course was getting dangerously close. So damn close we could read his Squadron letters, one of our own. I presume it was what we had got accustomed to, accepting the risks and taking it all in our stride.

Two of our Squadron did not make it back that night (was it shortage of fuel) and two diverted. And would you believe it, Stuttgart again the following night. This time a satisfactory fuel and bomb load. One of our engines had been playing up the previous night and it necessitated an engine change, so we had a replacement aircraft. I was shocked to discover it was the one Spiery had brought back all shot up from Dusseldorf on the 22nd April, with a patch on the starboard side where the cannon shell just about got me – Mac stressed on me not to be superstitious.

All went well on the outer legs, but we got coned by the searchlights on our run in. Six of them had us pinned down and one of our 250 lb. bombs hung up, so things were not looking good at all. Mac kept the bomb doors open, slung the kite into a vertical dive and evaded them. The bomb stayed put. We came out of the dive with one hell of a struggle and the pilot stated the aircraft was sluggish and that he had to juggle with the controls from then on. So we really struggled home at reduced height.

Over the Channel, I managed to release our hang up, so things were working out O.K. On landing, the aircraft swung all over the place, on to the grass verge and back on to the runway and we very nearly over-ran it. We wrote this one off with stress, even the fuel tanks shifted. Thanks again to the skill of Mac, we made it.

This was my second narrow escape in this aircraft. Glad there could not be a third.

28th July 1944. It was Hamburg and the most heavily defended target yet experienced, or possibly it was the way they routed us both in and out.

We ran the gauntlet of flak and searchlights and got buffeted about all over the place. The scene below was awe-inspiring. What a hammering this place took.

Our new aircraft was lettered ‘E’ and much to the annoyance of ground control, Mac always called up as ‘E’ for easy. She handled well and saw us through a few sticky situations.

On a very occasional weekend pass, it being too short a time to come home, London was the favourite playground. That is if you were prepared to accept the buzz-bombs and later, the V2 rockets. They would give us a bed down in the subway and many a tale I heard of suffering hardship and also witnessed first-hand. Nearest we came to coming a cropper was when having a meal in Bayswater late one night the window blew in and only the thick blackout curtains saved us from flying glass and the blast.

Back to daylights for our next three ops., end of July and beginning of August. After buzz-bomb and V2 bases, the Luftwaffe staying well away.

The 7th August saw us back on nights. ‘Mare de Magne’ the place. I think it must have been in support of our troops as the duration was only 22 hours 40 minutes.

It was around this time on returning to the `drome after a night out in Cambridge the workmen dropped me off the far side. Walking round the perimeter I could not fail to observe an American Liberator bomber in apparent difficulties, heading for our runway. He dropped like a stone 200 yards ahead of me. Luckily, I was on the edge of the tarmac and I threw myself into a slight dip. Just as well as they blew up and pieces of the plane and bullets (I still have some as souvenirs) fell around me.

I was untouched. I picked myself up, shaking a bit, and as there was nothing I could do to help, the crew being blown to bits, carried on.

We were rapidly becoming one of the most experienced crews of the Squadron, the choprate being what it was so it was only a matter of time before we took our turn as a co-ordinator of the attacks. On the 10th August we went to Dijon. We were briefed as the Deputy Master Bomber as standby for the Master Bomber.

To explain a little bit more. You flew around the target at low level, directing what target indicators to bomb, whether yellow, red or green. Your chance of survival lessened considerably, apart from the obvious, the biggest danger was from bombs and incendiaries being dropped on you from the main force above. In this instance, we got away with it and later on, we were instructed to drop our T.I’s and bombs and head for home, and damned glad to do so.

Two nights later, it was Ruselheim’s turn for a hammering – after the ball bearing factory, back in our normal role bombing on radar. Another very heavily defended place and we lost two of our Squadron that night. Some very good mates.

The Master Bomber was reported as saying they were more at risk at ground level from being peppered by ball bearings than enemy action! I had slipped off to Cambridge on the night of 14th August and on returning the following morning discovered we were off to St. Trond at daylight.

My crew had covered for me at the briefing so I had to grab my gear and get out to our aircraft to make my checks. In just over an hour, we were airborne.

An extremely interesting trip. Adequate fighter cover and no enemy to be seen. Very little ground defences. It was an airfield and I was doing the bombing, chasing my targets at random. I was spot on on every occasion. We were in high spirits, relaxed, and came down to sea level over the North Sea, skimming the waves and continued at low altitude over the coast.

Mac was in a playful mood, showing off his flying skill, getting rid of some of the frustration of night flying. We even got away with shooting up the Control Tower , super! Back to reality next night.

Off to Stettin on the Baltic. Our longest ever flight – tight on fuel – so I had to really watch it. We flew low over the North Sea , skimming the waves so that the German radar would not connect. Climbed to 20,000 ft., over the Danish coast and on to the target. It was not heavily defended and we had no bother finding it. It got a little bit monotonous on the long haul back and we were caught napping over Denmark.

The F.W. 190 came in from starboard bow up, spraying us with cannon shells and tracers and he completely missed! The mid upper Gunner had a go at him and reckoned he had a hit. We were now fully alert and prepared to take evasive action, but he never came back.

Being short on fuel, we throttled back to economise, made a slow descent and again made base with nothing to spare. On climbing out of the aircraft and standing back to have a look, she was a sorry sight. Holes in the fuselage, wings and tail, and yet the pilot never noticed any difference in her performance. The ailerons and flaps untouched – lucky again!

We had a break. It was nine days later on the 25th August, we went to Brest, allowing our Lancaster to be patched up and made serviceable. Our Forces were now rapidly advancing through France, leaving pockets of resistance behind and our task was to soften up the opposition. I must have had a spot of leave because by my log book it is the 20th September and back to

daylights.

This time Calais, and a week later, Sterkrade, both in support of our troops.

Surprise, surprise – the Flight Engineer Leader grounded me because, by his reckoning, I had reached the end of my extended tour of operations – this being done on a points system.

Meanwhile, the rest of my crew were still at it and I missed out on a good one. It was an island off the Dutch coast. The Germans were heavily fortified, so we breached the Walcheren dykes and flooded them out. They re-assessed my points and came to the conclusion I was one short so I still had another mission to do.

I had started at Stuttgart and I was to finish there, also on 19th October.

The Flight Engineer Leader had been flying with my own crew so there was no problem of going with strangers. Everything went straightforward enough until the target. We released our load and with the bomb doors still open, the flak got us.

The starboard inner engine burst into flames and the mid upper Gunner shouted out that his turret was covered in oil. I immediately feathered the prop, shut down the engine and the fire extinguishers worked and soused the flames.

The starboard outer engine was also playing up. The revs were fluctuating, but it kept going. Mac meanwhile was wrestling with the controls. The bomb doors would not close. Trying to get her on even trim and get the hell out of the target area where we were silhouetted against the glare. Again, his skill paid off.

We got away by losing plenty of height and could take stock of our predicament. We were losing fuel from the starboard outer so it was only a matter of time before I had to shut it down also.

God , these Lancasters could take one hell of a beating and still fly and this one did just that. We nursed it along on the two port engines and just made Woodbridge on the Suffolk coast.

We returned home by R.A.F. transport and Mac asked me to continue on operations to complete the crews quota, promising he would recommend me for

the D.F.C. What a decision to make and I turned him down. My nerves were shattered after thinking I had completed my ops., and had to do another and it turned out as it did. If he had asked me earlier, I know I would have done it and I have always regretted saying no. There was no second chance.

The good news was, they did complete their tour and the bad was, I completely lost touch with them. We functioned well together. Good blokes, great comradeship. You did your job and if luck was with you, you survived. I did not think so at that time, but later, I must have suffered remorse of conscience. I had let them down.

Chapter four

There were very few left of the original crew members who formed the new 582 Squadron earlier. They posted me to Brackla, and Aircrew Allocation Centre, near Nairn, on the Moray Firth. And, low and behold, I could not have got a better posting to 54 M.U. Cambridge, 1/2 mile up the Newmarket Road from where the lady friend lived.

On duty at my basic trade of Fitter Engineer, off duty retaining my rank of Warrant Officer. It was a ridiculous set up right from the start. I fell foul of the Corporal in charge of our squad. He had no time for aircrew, considering we got our rank too easy. So eventually, it came to a head. I got fed up with his bully tactics, told him to stand to attention when he was speaking to an officer ( and to get stuffed).

The “Chiefy” in charge of the Orderly room was a good bloke and saw the funny side of it so yours truly reported every morning and then had the rest of the day off. It was not such a good set up as I first thought. He had me down as Duty Officer once a week. We were billeted in Jesus College, in the old quarters. There was a low wall and high metal railings round the grounds. Just as well, because the Duty Officer and a W.A.A.F., N.C.O., rounded up the ‘ladies’ canoodling against the wall at 23.00 hours, mostly Americans, lots of coloured, rather tricky on occasions and then you sent for the M.P’s.

Anyway, one of those nights, after seeing my companion to her quarters, I was making my own way to bed, via the cloisters, and I saw a ghost. From the rectangular enclosure you looked down on the ruins of what had been part of the convent. It was midnight and I saw a white apparition moving about below. I flashed my torch and saw nothing and on putting it out, there it was as before.

I took to my heels and on bursting in to my billet, where my mates were playing cards, told my story to their disbelief.

Next day we made enquiries from the staff in the modern part of the College and they confirmed my experience. The old part of the place had been a convent, pillaged in Cromwell’s time and the Mother Superior was locked in her room to starve to death and now she walked the ruins.

In the dining room, above the door, there was still the small window where she had observed the nuns at work and the compartment where she was shut up. That is how it was told to me and, believe me, I saw no reason to doubt it.

There were lots of stories told about Jesus College. The W.A.A.F.quarters were in the ancient bit and certain rooms could not be slept in, they were so cold, even on the warmest nights.

I was the odds body N.C.O., I , and another , had to go to Cosford by rail to pick up a deserter. A Sergeant Air Gunner who went A.W.O.L. but no complications, he came back to his unit quite peacefully. Again, I had to take a squad on a combat course and show some initiative. We did quite well on that one. I must have been fit then.

One of the details I did not like was being in charge of a guard over a hospital patient. Four hours on, four off. He was a Sergeant. Same basic training as myself. Fitter Engines and how he got in the predicament he was in, was as follows.

He was a Welshman. Home town Cardiff, and he had served overseas in the Middle East. On getting a home posting, he was lucky enough to get a flight back, so arrived home unexpected. Everything appeared in order. His wife pleased to see him and his lovely 4 years old daughter, who was just a baby when he left.

He visited his parents the following day to learn that his wife was just a whore but this he was unwilling to accept.

He accosted her about it, but she strongly denied it. He accepted her denial and his leave passed pleasantly enough. It was only later, back on the Squadron, he discovered he had caught from his wife, venereal disease, syphilis – the worst. He did not report it or go sick and the worry of it all started to prey on his mind and his work deteriorated.

It came to the crunch one day when he was working on a gantry, the Engineer Officer turned up. He was told, in no uncertain manner, to get his finger out or else. He lost his temper, dropped the spanner he was using on the Officer’s head, came down the ladder and had to be forcibly restrained from doing any more harm. Of course, it all came out into the open then. He was getting treatment and awaiting his trial.

I got friendly with a Scots lad, also a patient, and he gave me his worries. He had served in North Africa and had met, courted and married a nurse, a South African girl – a beauty and her parents rich. He returned to this country and in some port got drunk, visited a brothel and also got syphilis.

He had the common sense to report sick and he was here for checks to see if he was cured. He said they strapped him to a moveable table, syringed off fluid from his spinal column for laboratory testing. The good news was, he could not infect a woman during sexual intercourse. The bad was, if he made her pregnant, the child would have it. He was in a quandary. He had a cable to say his wife was on her way to the United Kingdom.

I am sorry I do not know the outcome of either of these cases.

So, I never had it so good, but it could not last. The Unit was moving to Newmarket Heath and I formed part of the advance party in the Repair on Site Section. Got married on the 24th March, 1945 at the farm and lived out in Cambridge and latterly, Newmarket.

Only thing of any consequence I did was they gave me two old bombers – a Lancaster and a Halifax – to mark up, over at Snailwell, the other side of Newmarket. It was left to my discretion where to show on the outside of the aircrafts by stencil the best places to cut through and the position of axes, oxygen bottles etc.

The big day, when they collapsed the under carriage, smoke flares and a live crew had to be rescued by the local Fire Brigade, all good fun and games.

Things went along smoothly and if they had continued like that, fine, but it was the uncertainty of it all. I tried to get back flying in Transport Command – no joy. If I wanted to continue in the Service, I would drop in rank to Sergeant first and then a Board at my basic trade of Fitter.

In preparation for demob, I went down to Newmarket Station one day per week on clerical duties. I got to know most of the trainers, jockeys and stable lads , as a most meetings, it was a horse box special. In my office was a chap, Joe Harris, who owned two dress shops in Cambridge. Also there was a bookie’s clerk in civvy street, so we went racing to any meeting on the Rowley Mile.

`Honest Joe’ and his mates ((I did the running) and we cleared a packet at the Derby. Joe was a Jew. A likeable rogue . He must have had some good connections to have spent all his service in Cambridge and now Newmarket. He did not want promotion. A.C.2 was good enough. He drove into work every day in a Bentley.

After Arnhem, a flight landed each week with parachutes, somewhere in East Anglia and these were transported to London. Two were dropped off at Joe’s to be made into ladies’ lingerie etc. I got one to keep my mouth shut.

If you needed anything, clothes, chocolate etc…., he could supply. The Unit had a dump of crashed aircraft. He discovered a market from the local farmers for sections of gliders to use them as hen coops. If there was possibilities to make money , he exploited them, but I never did get too involved with him. Through my connections with the Stables, I took a considerable amount of cash from him on a bet and that put a damper on things.

So, life was interesting. We got a wee bit extra from the farm – butter, eggs and bacon – and our first child was born in June, 1946, at White Lodge Hospital.

Demob came in October of that year and it was home to Scotland and Civvy Street and I took badly to it.

I missed the Services so I enlisted in the R.A.F.V.R. on 19th March 1949 and always looked forward to my fortnight’s training every year. Flew in Lincolns and I did not think they were as good as the Lancaster. Later on, Washingtons (B.29) the R.A.F. version of the Superfortress.

My peak year was 1952, flying from 35 Squadron, Marham. I did two spells. What made it of special interest was that I was invited back to take part in an exercise, ‘Ardent’. I did my longest flight ever – 4.20 hours day and 6.00 hours night at one go. It was all completely different from war time. You computed everything before setting out.

The Washington was divided into front and rear pressurised compartments, joined over the bomb bay by a long tunnel. In the middle of which was an astrodome. It had been known to break and the unlucky person caught in between shot out like a bullet.

On my first fortnight that year, the company could not have been better. Another Reservist from Sheffield, who was a first-class pianist, and every night spent at the local. Everybody was so impressed by the talent of this chap, the word got around and the place was crowded out and the landlord showed his appreciation. Unfortunately, he could not make it second time round.

All good things had to come to an end. 1953 was my last year and I hung up my uniform for good.

Chapter five

In late 1989, through the local paper, I read that the Aircrew Association had formed a Tay Branch, so I enrolled. They have an official quarterly magazine called “Intercom” and I was pleased to read in 1990, of the Little Staughton Pathfinder Association’s Annual Reunion, 109 Squadron Mosquitos and 582 Squadron Lancasters.

Time was very short to join the Association and get details of the reunion, only a week away, so it was mostly done by phone. Anyway, I made it. On the Thursday, I motored down to my youngest daughter Jean’s home at Welwyn, 15 miles this side of London, as my base.

They had sent me their last two newsletters called “Illuminator” and among the list of membership were Splinter and Beryl Spierenburg, now resident in Oxford. By road back to Bedford on the Friday to the Moat House I met the Committee visiting R.A.F. Cardington for the aircraft exhibition.

Having been too late to book local accommodation and for the Annual Dinner on the Saturday, I went to the Remembrance Service at All Saints Church, Little Staughton, on the Sunday and lunch in the village hall. I was very hopeful of renewing old friendships and hearing fromSpiery’. What did happen that fateful night. (He was one of the standard bearers).

I introduced myself after the service, and was cordially received by both him and his wife,glad to know that I had survived the War. Unfortunately, they were returning to Oxford immediately and there was little time for conversation.

Shortly before they had visited France to pay their homage at the graves of our three wartime comrades, ( see the Illuminator for August 1990) with Bill Foley, the Aussie (more about him later).

All he would comment on that terrible night was that prior to take-off, they shook his hand and said their last farewells. How did they know they were not coming back?

Was it because I was no longer a crew member. I asked him to write me and for Bill Foley’s address, but he never did, only exchanging Xmas cards.

At lunch, I carefully studied the gathering, looking for familiar faces, but without success. I was very disappointed. Surely some of the members of ‘Mac’s’ crew were still alive. To complete that Sunday, I drove to Newmarket and on to the farm at Stradishall to see my late wife’s sister and brother and laid flowers on her grave.

It was good to hear Bill Foley was still alive. I had made enquiries during my tour of Australia to no avail. He had come home with me on leave when we were flying to meet my father, who was born in Australia. It was on the Richmond River at a place called, Broadwater N.S.W., a small world -Bill – a school teacher, had taught there.

The following year, 1991, I was unable to attend the Reunion because of ill-health.

1992 was the 50th Anniversary of the Pathfinder Force and I was not going to miss that one. So, I booked my hotel accommodation etc., in plenty time and I went down by rail, arrived Bedford Moat House the evening of Friday, 14th August and spent a pleasant night in cordial company chatting about old Squadron times.

Saturday, over to R.A.F. Wyton for the Grand Reunion Day,. All the 8 Group Squadrons represented and wartime friends from all over the world reunited. They did us proud. Each corner of the hangar drink in abundance and a buffet lunch. The Band of the R.A.F. College, Cranwell, playing. Flying displays by the “Red Arrows” and a Mosquito and Lancaster which brought back war time memories. All in all a very satisfactory day.

The present-day R.A.F.personnel treating us old comrades as V.I.P’s. Back to the hotel for dinner in the evening, hosted by the Mayor of Bedford and other dignitaries. A Canadian couple, (he a pilot ex 109 and she a W.A.A.F at Little Staughton), a war time romance, knew Mac’ (F.L.Magee) well and were sorry to hear he had died a few years earlier.

Unfortunately, Spierenburg was taken ill just before the Reunion and his place was taken by another Dutchman from 617 Squadron, his friend and service compatriot.

By chance, we were at the same table and when I mentioned I had been his Engineer, we conversed. He told me he and Spiery had joined the R.A.F. together, Spiery having been in the Merchant Navy and torpedoed twice. They had gone through basic training and their Pilots’ course and then went to separate Squadrons.

It was true that Spiery made his way back to Holland after the crash but was eventually betrayed to the Germans. The Gestapo did not believe his story of being an R.A.F. pilot and he was sent to Buchenwald. We know now that it was a death camp. How he managed to talk himself out of there, only he alone knows. They met again after the war, being duty-bound to return to the Dutch Air Force. Spiery joined Phillips Electrical and convinced them to buy their own aircraft and he became a millionaire.

Still an awful lot of blanks to fill in. Maybe this year I will get the full story.

I was able to get some statistics of our bomber losses and how dicey it was during the period I was flying operational. `56 Squadron Worboys, for example; ninety three 7 man Lancaster crews posted to this Squadron between June 1943 and the move to Upwood in March 1945, only 7 crew members survived.

A few, very few, crew members from the missing aircraft became prisoners of war. The majority perished. I was unable to get the figures for my own 582 Squadron but I know it was just as bad. Somebody was looking after me!

December ’43, when I joined the complete crew at Stradishall, 97 Squadron at Down had an appaling night. Lost one Lanc over Berlin and seven crashing in the fenland fog on their return. Fortynine men killed and six injured. That was only a wee bit of the tragedies of that night. They called it ‘Black Thursday’.

It was common practice for the Commanding Officer to do an operational trip occasionally and No. 7 Squadron at Oakington lost three C.O’s in succession during the dark days of late 1943 and early 1944. Our own C.O. doing his stint as Master Bomber , came back with incendiaries sticking out of his fuel tanks. Luckily, they did not go off and the tanks self-sealed, quite a miraculous escape.

Looking back, apart from the enemy action against you, the things to be really apprehensive about were icing-up, the extra weight on your wings.

Also moonlight nights when you could only hope for cloud cover to evade the night fighters. You were up against the elements as well. No wonder we lost so many aircraft, the odds being stacked against us.

To come back to the 50th Anniversary of the founding of the Pathfinder Force, Sunday 16th August saw an act of Thanksgiving Service being held in Ely Cathedral and a very moving one it was.